What Is Koku? Relationship between Palatability and Koku

Koku is not just about palatability. Koku is constantly misrepresented.

Koku is often written in katakana these days, but it is believed to originate from the Chinese word “酷” The Kojien dictionary (seventh edition) defines it as “a deep and rich flavor of things such as sake, representing the ripeness of the grain.” However, Professor Nishimura points out that the latest studies suggest a definition that varies from Kojien.

“The words used to represent palatability uttered by commentators on TV food shows are actually often incorrect. Koku doesn’t necessarily mean delicious, and koku and strong umami flavors aren’t the same either.

Palatability is a subjective assessment that differs from person to person, but the professor says the sensations of umami taste and koku are objective assessments. What are the differences between umami taste and koku, then? Umami taste is a basic one, and has become a universal word in recent years. Sodium salts of glutamic, inosinic, and guanylic acids give us the typical sensation of umami taste discovered by a Japanese scientist. Meanwhile, koku sensation is not determined by one specific compound. Prof. Nishimura has been studying koku for the past ten years and defines it as follows:

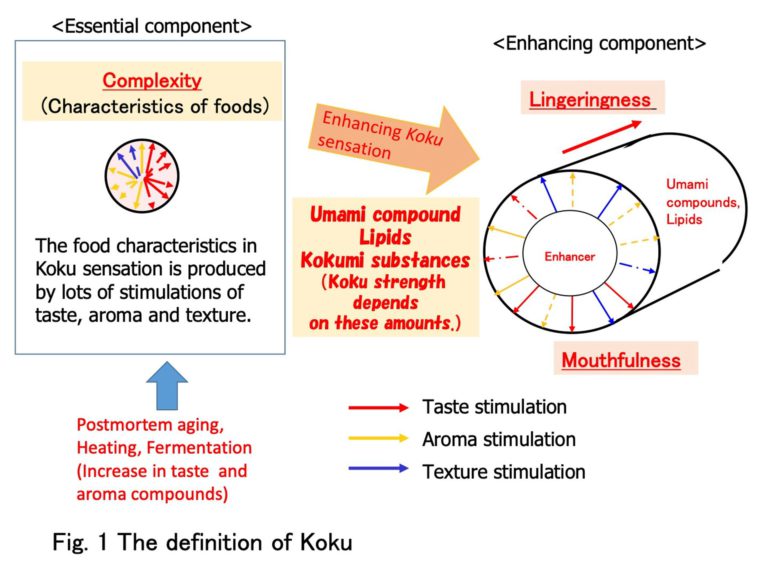

“Koku is a whole sensation caused by many stimulations in terms of taste, aroma and texture. Koku is a phenomenon formed by the complexity of the stimuli, the spreading of this sensation and its lingeringness.”

In other words, just as taste sensation is defined by five basic flavors—sweetness, saltiness, bitterness, acidity and umami taste—Professor Nishimura states that three basic components can represent koku sensation. In short, koku sensation is represented by the strengths of three components: complexity, mouthfulness, and lingeringness.

What are the three components that create deep, rich koku?

The English words for the three components of koku are understood overseas. However, since no single English word represents all three components, Professor Nishimura published his paper, “KOKU.”

“The word ‘body’ used in the world of wine is a concept quite similar to koku. For example, a person who likes tonkotsu ramen may find soy sauce-based ramen too light and lacking in koku. However, soy sauce also has koku, though not as much as pork bone. Koku can be weak and strong, and its optimal value varies depending on the food, dish, and individual’s dietary habits and preference,” says Professor Nishimura.

Complexity is the first component of koku. It can be objectively evaluated by the type of compounds contained. For instance, fermented foods such as soy sauce and miso age for two years rather than one year, and the longer they age the more hundreds of compounds they produce.

“Generally, the longer the cooking time, a wider variety of compounds are produced, making the dish more complex. This is the mechanism that makes many stewed dishes seem stronger in koku,” says Professor Nishimura.

The second component, mouthfulness, involves a retronasal aroma, the aroma sensation that spreads from a person’s throat to the nasal cavity when one swallows food.

“Retronasal aroma is an important element for determining food’s palatability. We can’t sense what we’re eating when we have a stuffy nose from a cold, but that’s because we cannot use our olfactory senses. It is believed that our olfactory senses are more sophisticated than our sense of taste, so they are likely to sense differences in a more complex way,” says Professor Nishimura.

For example, secret ingredients, such as a dash of instant coffee in a curry, enhance the breadth of flavors and deepen koku.

The third is lingeringness. Fat helps to make it more pronounced. Aroma compounds dissolve easily in fat and are perceived as lingering aroma as they stay on the tongue and nose’s mucous membranes.

“We often say, ‘It’s fatty and tasty,’ but fat itself is tasteless and odorless. It seems delicious because a variety of compounds are complexly bound with fat through cooking,” says Professor Nishimura.

When we understand these three components that create koku, we will be able to make full use of them in making satisfying and healthy dishes, even if we reduce the salt content.

Koku sought by a famous Japanese restaurant

Koku in Japanese food is subtle compared to Western-style dishes such as those made with bouillon and stews.

Hayahisa Osada, the owner of Nihon Ryori Itto and director of Washoku Japan, says, “Koku in Japanese cuisine is complex.”

“Japanese cuisine is based on cooking with kombu and bonito dashi (palatability created by the synergy of umami compounds such as glutamic and inosinic acids), but cooking vegetables in dashi produces more dashi from the vegetables, forming complex palatability and koku. Cooking fried food in dashi also gives a dish extra koku. Buddhist vegetarian dishes with no meat or fish are made more satisfying by increasing the palatability and koku by umami compounds and flavors in layering kombu, shiitake and vegetable dashi and using fat effectively,” says Osada.

Osada hails from Hekinan, Aichi Prefecture, which has a food culture that involves using a variety of seasonings, including haccho miso, white soy sauce, Mikawa mirin and kasuzu (sake lees vinegar), and is well-versed in the use of seasonings. He says that traditional fermented seasonings are packed with the wisdom of our forebearers, who produced them to add koku to food.

“Take miso, for example. According to the “Sa-Shi-Su-Se-So of cooking,” [sato (sugar,) shio (salt,) su (vinegar,) shoyu (soy sauce) and miso], it is used as the last ingredient in cooking. It is usually said that it shouldn’t be boiled as it will lose its aroma, but bean miso such as haccho miso, which has been aged longer, is robust and increases flavor when stewed. In its production region, the use of bean miso in miso katsu and stewed offal is a popular way of reducing the ingredients’ peculiar smell and increasing their koku.

For this issue, Osada introduces recipes for Kanto-style zoni (mochi in soup) and mackerel simmered in miso, as typical home-style dishes in which koku holds the key.

RECOMMENDATION RECIPES

A dish with deep koku produced by the flavor of dashi and savoriness of mochi.

RECOMMENDATION RECIPES

Mackerel and fermented seasoning give this dish outstanding koku and depth of flavor.

Osada also prefers using taihaku white sesame oil (pressed from raw sesame seeds) and rapeseed oil pressed the old-fashion way to increase koku in his cooking. He uses fat with a clean aftertaste in deep frying and mixed rice dishes to add koku.

“I also give a stewed dish koku by adding broiled fish bones or eel’s head. Nori is also useful. You can add koku to dishes simply by toasting nori (seaweed sheet) lightly to bring out the aroma to wrap rice balls or broiled mochi, add it to ochazuke, miso soup, or clear broth,” says Osada.

How about making a little effort at home to rediscover the koku of Japanese cuisine?