One Day, One Layer at a Time. Natural Ice Created by Nikko’s Exquisite Water.

Nikko’s food culture is nurtured by exquisite water from the mountains

The city of Nikko is located in the northwestern region of Tochigi Prefecture. With a total area of 1,450 square kilometers, it is one-fourth of the prefecture’s land area, of which 90% is covered by forests. The mountainous areas are over 2,000 meters high, and the terrain has large undulations compared to the flat urban areas, which are about 200 meters above sea level.

Mt. Nantai, which forms part of the mountainous region, is one of the city’s most famous mountains. It lies northeast of Lake Chuzenji and is sometimes called Nikko Fuji for its graceful conical shape. The Nikko mountain range, which consists of Mt. Nantai, Mt. Nyoho, Mt. Omanago, and so on, has been an object of mountain worship since ancient times, and the mountains themselves were considered sacred.

Springwater and snowmelt from the mountains flow underground and bring clean water to the entire region. Such exquisite water is essential for producing local specialties such as rice, sake, buckwheat noodles, and yuba (tofu skin). Nikko’s food culture has been nurtured along with its famous water.

Nikko's ice farming starts with preparing the soil

Natural ice—with a history of over 100 years in Nikko—would not be possible without its famous water. Natural ice refers to ice made by taking advantage of the changes in temperature during the winter. It was valuable not only for food but also for food preservation and medical use in the days when there were no refrigerators.

Ice farmers are called himuro. There were nearly 100 himuros throughout Japan in the early Showa period (1926–1945), but today, the numbers have dwindled to five with the development of mechanical ice-making and refrigeration/freezing technology. Three of the remaining five are in Nikko.

“The weather has a direct impact on ice-making. We’re constantly on our toes every year.”

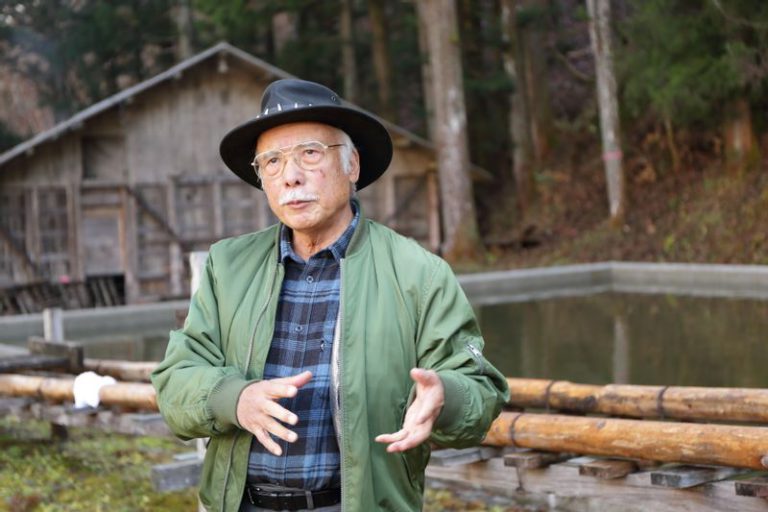

So says Yuichiro Yamamoto, the representative of the himuro Yondaime Tokujiro. As with the other two himuros, Yondaime Tokujiro uses an ice pond to produce ice. The 15-meter long, 30-meter wide, 50-cm deep stone-build reservoir is lined with soil at the bottom, just like a farm field.

At a glance, it looks like a shallow pool. Springwater from the mountains is drawn into this ice pond to make ice. Surrounded by trees, the ice pond is shaded throughout the year, and it gets colder than the surrounding area in midwinter. The environment is perfect for producing ice.

“First, we begin the soil preparation for the ice pond in the fall. Ice freezes downwards from the water’s surface, so hard bottom soil impedes ice formation. That’s why we need to till the soil beforehand. The pond water starts freezing around December, but the ice at that time of year is soft with a lot of impurities. We can’t sell it, so we smash everything and throw it away,” says Yamamoto.

Ice-making goes into full swing from January to February, the coldest months of the year. Water is collected in the ice pond when the atmospheric pressure is read and a cold spell is detected. Ice is grown over a two-week period.

Ice grows by about one centimeter a day. They are not out of the woods yet, even if the ice grows to a certain thickness. They have to sweep the surface of the ice with a broom every morning to remove dust and debris. The falling snow is also an archnemesis. Snow not only contains dust, but it also melts the surface of the ice if left unattended. The year 2016 saw an exceptional amount of snowfall, so Yamamoto and his men had to sweep over the ice for 18 straight hours.

Once the ice has grown to about 15 centimeters thick, it is time to cut it for harvesting. The work begins in the early morning, with Yamamoto, his son Jinichiro, the staff of the restaurants that buy the ice, and volunteers working as a team. The entire process of cutting the ice with a power cutter, pulling it out of the water, and storing it in the himuro (or ice storage house) is done manually.

Covering the ice with sawdust is an old-fashioned method of preserving ice. The sawdust absorbs the surface moisture and prevents the ice from melting.

“When the ice grows well, layers form on its cross-section. One day, one layer at a time; that verifies the time and effort we put in. The ice-making method of utilizing radiative cooling, in which heat is emitted from the ground surface, produces ice that’s harder and less likely to melt than ice made by machines using cold air. The transparency of the ice, so clear that you can see right through it, would also be hard to replicate with mechanical ice-making,” says Yamamoto proudly.

Nikko’s original scenery is handed down to future generations

Yamamoto took over as the fourth successor of the himuro in 2006. He used to operate Chirorin Mura, a leisure facility on the Kirifuri Highland in the city. Ryoji Yoshiara, the third successor of Tokujiro, supplied ice for the café in the facility.

Natural ice has now become a Nikko specialty, but it was in its twilight years then. Yoshiara, who was already approaching advanced age, felt he had reached the limit of his operations and decided to wind up the business at the end of that year. When Yamamoto heard about this secondhand, he went directly to Yoshiara to negotiate. He offered to take over the himuro.

“A decade ago, you could buy natural ice for a few hundred yen at a supermarket in the city. The locals didn’t realize its value. That led to its decline, but it was such a shame to let the business fold. The scene of cutting out ice is a winter tradition in Nikko. It’s a culture that can be regarded as an original scenery,” said Yamamoto.

Yamamoto expressed his thoughts, but Yoshiara did not approve so easily. However, Yamamoto did not throw in the towel. Day after day, he visited Yoshiara to persuade him. A few weeks later, Yoshiara finally caved after repeated pleas from Yamamoto. Yoshiara accepted Yamamoto’s taking over the business, provided he would only offer advice and not involve himself in work.

“At first, I thought that filling the pond with ice would create ice, and I didn’t realize the amount of effort involved. Although I made ice, I had almost no buyers,” recalls Yamamoto.

The turning point came in 2008, when he and a group of volunteers exhibited at a food trade show in Tokyo to promote the natural ice brand. The measure was taken to avoid competition with the other two himuros, but his speculation of demand in Tokyo was right on the money. The ice caught a buyer’s attention, and shaved ice made of natural ice was sold at a Tokyo department store for a limited time.

“If we’re going on the offensive, [we thought] let’s aim for the capital and eventually go to Rome, Italy! We had big dreams. We used richly flavored syrups made with locally-sourced strawberries and blueberries for the shaved ice. We wanted to impress people who thought shaved ice is for kids,” says Yamamoto.

Shaved ice made from natural ice has a texture like cotton candy, and it has captivated many people. The timing of the launch coincided with the G8 Hokkaido Toyako Summit, which focused on global environmental issues, and the shaved ice attracted public attention as an eco-friendly treat. Also, thanks to the shaved ice trend of the 2000s, the world became aware of the outstanding quality of Nikko’s natural ice.

“The success of natural ice was due to consumers embracing the ice-making process and culture,” recalls Yamamoto. We asked him about what has kept him going during the 15 years since he took over from the third successor.

“That would be the joy on the faces of those who eat the ice. Both grown-ups and kids look impressed, and their hands stop for a minute. I feel that my hard work has paid off when I see such scenes. I can leave the ice-making mostly to my son, so that’s a relief for now. I want to continue to share the flavor of Yondaime Tokujiro, and Nikko’s culture, by extension, with as many people as possible,” says Yamamoto.

Shaved natural ice melts quickly in the mouth. The history and culture of Nikko, passed down from generation to generation by the himuro, are condensed in that moment of coolness. It tastes even better when you understand and appreciate the process of ice-making.