The Sushi Culture Continues to Evolve with the Times and Social Climate

For this article, we asked the sushi research authority Terutoshi Hibino about the history of sushi and the food culture across Japan related to sushi.

The roots of sushi—it is not a traditional food originating from Japan

“The widely-accepted theory states that narezushi, the precursor of modern sushi, was created by paddy field farmers in areas such as Laos of the middle reaches of the Mekong River in South-East Asia. The food came over to mainland China and is said to have reached Japan as a court offering during the Muromachi period (1333–1573),” says Hibino.

Narezushi is fish treated with salt and fermented to preserve it, with no vinegar used. Narezushi includes, from the oldest, honnare, kodai namanare, and kairyo-gata namanare. Of these, funazushi, which is equivalent to honnare, from Shiga Prefecture is said to be one of the oldest types of sushi that still exists. Furthermore, iwana-zushi from Gunma Prefecture is equivalent to kodai namanare. Both types are made only with fish, salt and rice, and fermented until the rice is uneatable. Narezushi is eaten in various areas of Southeast Asia ever since its origination up to the present, but it went under a unique evolution and change after coming over to Japan.

Lineage and types of Japanese sushi

Significant developments in sushi were seen after the start of the Muromachi period. Hibino says that this is because rice entered the common person’s diet at that time.

“The middle of Edo period (1603–1868) was a time in which commoners were full of life and free. Common people are adept at simplifying things to meet their daily needs, so they orchestrated ways to prepare sushi that was quicker to make than narezushi, without resulting in wasted rice.”

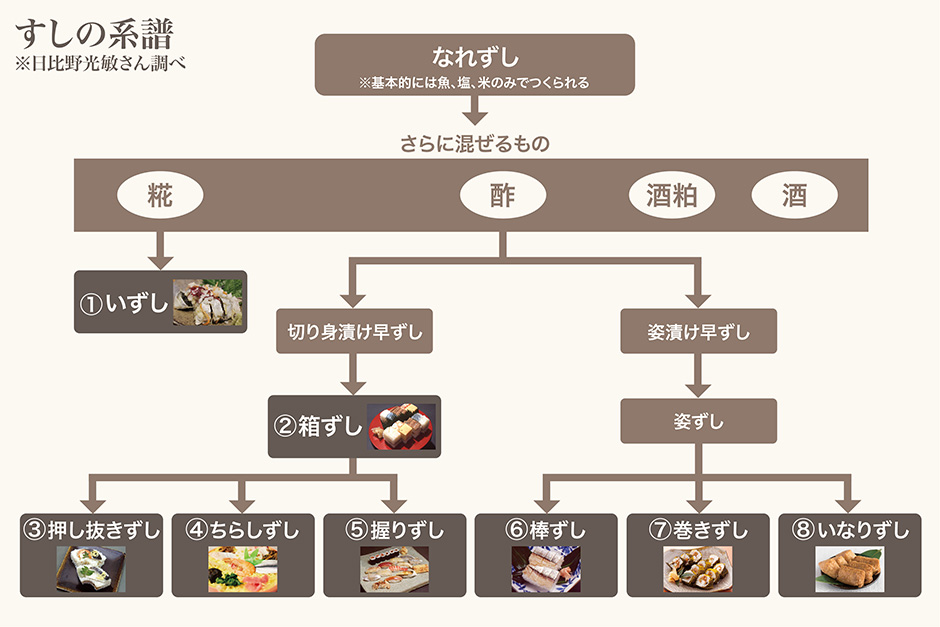

Allow us to introduce the eight types of sushi (numbered 1–8) on the lineage chart, along with their current equivalent, according to Hibino.

1: Izushi : Hatahatazushi (Akita Prefecture)

Izushi is narezushi made with only fish, salt and rice, and evolved further with the addition of malted rice. This type of sushi has spread across Japan as a New Year’s dish. Along with hatahatazushi, the kaburazushi of the three Hokuriku area prefectures, and the nezushi of Gifu Prefecture are also New Year’s dishes. Additionally, izushi has established itself across Hokkaido. It can be said that this sushi culture is focused on areas facing the Sea of Japan.

2: Hakozushi : Kamigatazushi (Osaka Prefecture)

Hakozushi is made by filling a square wooden box with sushi rice and adding toppings before pressing down to mold the sushi. Kamigatazushi is assorted Kansai-styled sushi based on hakozushi, created by Osaka merchants and featuring luxury ingredients such as shrimp and sea bream. This type took sushi, which was an extremely cheap food up to this point and promoted it to an extravagant luxury dish by applying various techniques. For this reason, it is said that hakozushi evolved the most in the Osaka area.

3: Oshinukizushi : Sawara-no-oshinukizushi (Kagawa Prefecture)

This sushi is prepared in the same way as hakozushi; however, oshinukizushi does not use a knife. Oshinukizushi used to be sushi that was placed in square molds and pushed out. Molds shaped as fans, pine needles and plum blossoms as seen in the photograph are said to be comparatively new customs.

4: Chirashizushi : Matsurizushi (Okayama Prefecture)

Chirashizushi features colorful topping ingredients scattered upon sushi rice. Various types of local dishes using both mountain and ocean ingredients have been born in Okayama Prefecture, an area with an abundance of nature sandwiched between the Chugoku Mountains and the Seto Inland Sea. One of these local dishes is matsurizushi (or barazushi). It is said that this sushi is popular for ceremonial occasions or to entertain guests.

5: Nigirizushi : Edomaezushi (Tokyo Prefecture)

Edomaezushi represents the nigirizushi type, in which bite-sized “in-season” seafood called neta is placed on sushi rice and shaped by hand. Although in modern day, nigirizushi with raw neta is popular, but edomaezushi features neta that has been pickled, salted, boiled or broiled.

6: Bozushi : Sabazushi (Kyoto Prefecture)

This sushi makes most of the shape of fishes and molds it with sushi rice into a rod shape. Kyoto sabazushi was originally prepared with only pickled mackerel and sushi rice, but now, the sushi often features a thin slice of kelp as well. This sushi features kelp transported by matsumae boats, hence the name matsumaezushi.

7: Makizushi : Takanamaki (Oita Prefecture)

This sushi rolls ingredients such as sushi rice, toppings with laver using bamboo sushi mats before cutting into bite-sized pieces. The image of sushi rolled in laver prevails for makizushi, but this type of sushi is rolled with takana (leaf mustard) in Oita Prefecture, seaweed in the Kansai region, and kelp in Wakayama and Kochi Prefectures. It is believed that people used ingredients that were most easily procured in their region for rolling.

8: Inarizushi

This sushi was born at the end of the Edo period. It features sushi rice stuffed within deep-fried tofu pockets that had been simmered with soy sauce, soup stock and sugar. While this sushi is roughly the same across Japan, the deep-fried tofu pocket shapes to the west of the Sekigahara area of Gifu Prefecture are triangular, whereas areas to the east of Sekigahara often had square-shaped pockets. Another feature is that chirashizushi is often stuffed into triangular pockets, and white rice or white rice with sesame seeds are often stuffed in square pockets.

Freely evolving sushi that corresponds to the times and social climate

As we can see, there are many variations of sushi, but the most popular sushi could be said to be, without a doubt, nigirizushi. The backdrop of its popularity lies in post-war Japan, when there was a tight control on food, which caused people to flexibly adapt to it, says Hibino.

Post-war Japan suffered from a serious lack of rice, causing the Emergency Restaurant Business Measures Ordinance to be proclaimed in 1947, prohibiting rice from being served in restaurants. In this dire situation, Edomae sushi shops declared that, “Cooking rice that customers bring to the shop and making sushi means we are only processing food.” The Tokyo Prefectural government accepted this claim, and it gradually spread all over the country. The rule decided at this point, “Ten pieces of sushi are to be made from one go (approximately 150 grams) of rice” is the basis of modern sushi sizes. The Emergency Restaurant Business Measures Ordinance was lifted in 1949, but the nigirizushi culture that had spread throughout Japan stayed strong. In this way, the notion that “sushi equals nigirizushi” has been deeply rooted in the society to this day.

Meanwhile, there are some types of sushi, such as the Ishikawa Prefecture’s mattozushi, that does not exist anymore.

“The reason why I persist on having elderly ladies across Japan make local sushi for me to record is because I fear that there may not be as many types of sushi left in 20 years like we have now. If somebody has experienced eating a type of sushi, just even once, I believe that the sushi will be handed down to the next generation.”

This is also why Hibino urges overseas visitors to try and recreate the sushi they had in Japan back in their own country. Even if the same ingredients cannot be found, he says attempting to make sushi with available ingredients is important. Even if the result is not the same as the original sushi, it is better than having that type of sushi die out. Hibino says that he is very interested in how sushi is evolving in a distinctive way overseas.

The sushi culture has been loved by many, freely evolving according to the times and social climate. This culture is nurtured by the simple wish of wanting to eat sushi, and we believe this desire will continue to weave the sushi culture toward the future as well.