Enjoy the Change of Seasons: Equinoctial Botamochi and Ohagi

The culture of ohigan, born out of the marriage between Buddhism and indigenous Japanese beliefs

“The term ohigan comes from Buddhism, but the practice of visiting graves and making offerings is unique to Japan and not to other Buddhist countries,” says Okubo.

In contrast to the shigan of this world filled with suffering and earthly desires, higan is a place where one reaches enlightenment. It symbolizes the completion of enlightenment, and the Japanese seem to have associated higan with the Pure Land Paradise. The ancient Japanese worship of the multitudinous gods of nature and the sun, combined with the Buddhist idea of the Western Pure Land, led to the days of the vernal and autumnal equinox when the sun sets exactly to the west being regarded as the periods when the distance between this world and the Pure Land Paradise is closest.

There are various theories about the origins of ohigan as an event. According to one theory, the first such event in Japan was the higan-e held in 806, and it seems to have started as an event among magistrates as a means to rule the masses through Buddhism.

“In the age of aristocracy, it was more of a Buddhist ritual. It wasn’t until the Edo period (1603–1868) that it spread to the common people, and the relationship with ancestral worship became stronger,” says Okubo.

Since ancient times, Japan has been an agrarian society, and many events have been held to mark the changing of the seasons. When the ritual practiced among the aristocracy and the samurai class spread to the common people in the Edo period, it became associated with folk festivals where people offered seasonal foods to the gods and enjoyed eating them with their families and relatives. It is believed that the interpretation changed to the notion that by offering prayers to the gods and eating together with them during higan, one can deepen their connection with the gods and Buddha and enter the Pure Land Paradise. It is not difficult to imagine that sharing the annual event of meeting the ancestors in the village helped maintain and strengthen the community necessary for farming in rural communities.

“Incidentally, obon and New Year’s are the days when ancestors return to this world, but they don’t come back on ohigan; we just pray for them. It’s like we have a face-to-face with them,” says Okubo.

Botamochi and ohagi: born out of the Japanese belief in offerings

The concept of offerings is also unique from country to country, and it differs between China and Japan. For the Japanese, offerings were a way to pray to the gods for the rice harvest, and the Heian nobility formalized it as a Buddhist ritual. White rice became the object of worship as something pure, and primarily rice, glutinous rice, sake and salt were offered.

Okubo says, “Japan has a ‘mochi culture’ where sticky foods are preferred. In China, mochi refers to food made of wheat flour, but the Japanese preferred mochi made of white, sticky glutinous rice as the very best offering.”

However, making mochi is a lot of work. On the other hand, dumplings made of non-glutinous rice flour are less sticky and easily made. It is likely that the way of making botamochi and ohagi by blending and mashing glutinous rice and non-glutinous rice spread widely because it was easier than pounding 100% glutinous rice with a mallet. In addition to the higan festival, botamochi and ohagi were made to celebrate births and handed out to neighbors.

There is also a reverence for red and white, as seen in the combination of the colors, and azuki is an ingredient often used in offerings. It is believed that the original form of botamochi came from the white mochi or dumplings offered to the gods, Buddha and ancestors, retrieved and dipped in red beans for people to eat. Botamochi was one of the foods handed out not only during ohigan but also on other celebratory occasions.

Botamochi and ohagi enjoyed outside of the ohigan period

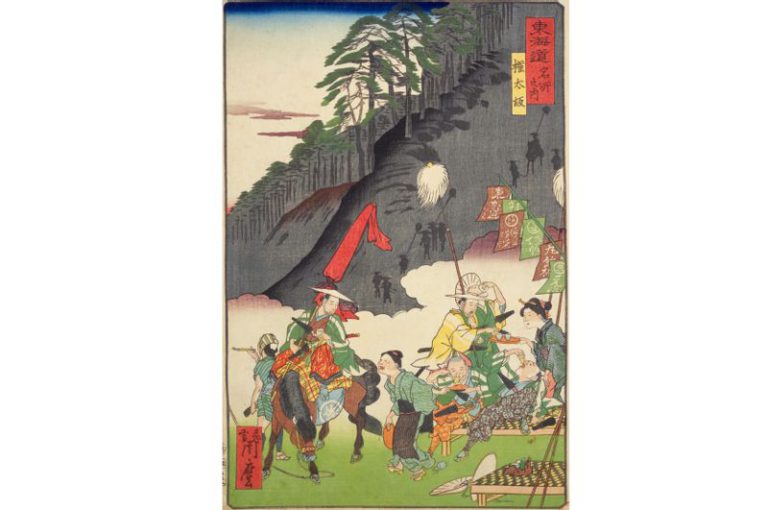

出典:国立国会図書館デジタルコレクション

There are records of people eating botamochi and ohagi outside of the ohigan period in various parts of Japan.

Gontazaka Hill — The Scenic Places of Tokaido — (1863): ukiyo-e illustrating the 14th Shogun Iexxxexcludexxxmochixxxexcludexxx going to Kyoto, showing samurai being served botamochi and tea by women in the teahouse.

“The picture of Gontazaka Hill depicts botamochi dusted with soybean flour. The Joeiji Temple in Kamakura, Kanagawa Prefecture, holds a ceremony to commemorate botamochi as an event associated with Nichiren. They prepare many black sesame botamochi for the event and distribute them on September 12. It seems there are many botamochi that have nothing to do with ohigan. Also, all kinds of paste are used. It was more often called botamochi than ohagi among commoners in the olden days. It seems that it’s more commonly called ohagi these days.”

What is the difference between botamochi and ohagi?

一説によると、こしあんがぼたもち、つぶあんがおはぎ

Depending on the region, there are various theories about the difference between botamochi and ohagi.

It is often said that the names derive from the seasonal flowers: bota(n)mochi from the peonies for the vernal equinox, and ohagi from the bush clover blossoms for the autumn equinox.

There is also a theory that botamochi is made with koshi-an and ohagi is made with tsubu-an. This theory stems from the fact that azuki beans are harvested in the autumn, and it became mainstream to use them whole during this time, when the skin is still soft; otherwise, they are sieved when the skin has hardened in the spring, half a year later. Another theory is that botamochi is made by cooking glutinous rice and non-glutinous rice at a ratio of 8 to 2 and that ohagi is made using only non-glutinous rice.

Also, although there are now considered sweet treats, it is believed that they tasted very differently.

“White sugar was a precious commodity in the Edo period, so they were probably salted. Some regions used salted bean paste until the 1960s. They became sweet only when white sugar became available during the Meiji era (1868–1912). Also, it was only in modern times that different types of beans besides azuki were introduced to make the paste, and a rich variety of flavors became available,” says Okubo.

Kinako (soybean flour) is relatively traditional, but other flavors such as black sesame seeds, aonori (green laver), and zunda (mashed edamame beans) are flavors popular in different regions.

Botamochi and ohagi have been part of the food culture loved continuously by the Japanese people. Let us imagine our forebearers who created the tradition as we savor them today.