Enjoying the Go-sekku (The Five Seasonal Festivals): May 5, Tango no Sekku

This time, we visited Hiroko Okubo of The Washoku Association of Japan, to ask about the backdrop regarding the popularity of the Five Festivals in Japan and how “Tango no Sekku” was celebrated throughout Japan as one of the seasonal festivals.

The Washoku Association of Japan (Abbreviated as: Washoku Japan)

Go-sekku generally refers to the five festivals of Jinjitsu no Sekku on January 7, Joshi no Sekku on March 3, Tango no Sekku on May 5, Shichiseki no Sekku on July 7, and Choyo no Sekku on September 9.

The Go-sekku originated from traditional events in China. The yin/yang philosophy of China, which has odd numbers as being unlucky, says that days featuring both odd day and month numerals on the calendar as “unlucky days,” and days to stay indoors. As these traditions came over to Japan, the Japanese culture and traditions mixed with these “unlucky” days, adding the distinct Japanese culture of driving out evil and celebrating seasonal turning points. This created a unique series of Japanese events that spread throughout the country.

The word sekku was used, which means food for offerings.

The Go-sekku are said to have come over to Japan during the Nara (710–794) and Heian (794–1185) periods, initially as functions observed in court by aristocrats. As Japan shifted to a samurai government, the sekku events permeated throughout the warrior class as well, as they learned the customs from noblemen.

It was not until the Edo period (1603–1868) when these events started to become popular among common citizens, when the Tokugawa shogunate established the Go-sekku along with New Year’s Day, January 1 as national holidays. It is said that January 1 was originally the day for “Jinjitsu no Sekku”, but as New Year’s celebrations became popular, Jinjitsu no Sekku was moved to January 7.

“The firm reign of the Tokugawa shogunate continued for more than 200 peaceful years during the Edo period, even though there were natural disasters, hunger and social classes. There are various theories on why the government established the Go-sekku. However, one theory says that as the townsmen culture blossomed, the government may have meant these seasonal festivals to be shared with commoners as a type of a social welfare activity,” says Okubo.

After this, in 1873 (the sixth year of the Meiji period (1868–1912)), holidays were enacted anew under the Meiji law. With this, the Go-sekku were no longer holidays, but some events of the Festivals continued to be celebrated among citizens as seasonal events in their daily lives. This continued after the Meiji period as well.

*In 1948 (year 23 in the Showa period (1926–1989)), the national holidays law was established after World War II, and only May 5 was reenacted as the Children’s Day holiday.

According to one theory, the Go-sekku culture made its way into the common citizen’s life because it happened around the time of rice farming. It is said that these festivals were easily incorporated into the people’s lives at that time, as rice farming was their lifestyle. On the other hand, the Go-sekku did not take root in some regions that already had different traditions related to rice farming.

“To the common people, seasonal festivals offered a day of celebration in which special food adorned the table. In the Edo period, the commoners had a very basic daily diet, so having special celebratory foods at seasonal festivals was a way to take nutrients they lacked on ordinary days. I believe these events were rare occasions to feast for these people, and that they probably looked forward to these events very much.”

From an event to ward off evil to an event celebrating the growth of boys

Of the Go-sekku, currently, “Tango no Sekku” is the most prevalent in the Japanese citizen’s life.

The seasonal festival culture from ancient China has seasonal flowers according to each event. “Tango no Sekku” is also called the Shobu no Sekku (Acorus calamus Festival), in which some events include drinking medicinal liquor with immersed Acorus calamus , decorating entrances with Acorus calamus and taking Acorus calamus baths, in order to ward off sicknesses and misfortunes.

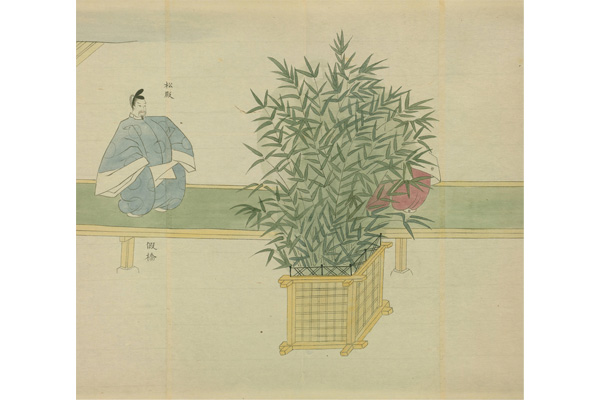

As time went on the word Shobu started to conjure up other meanings such as “winning” and “having a martial arts spirit,” which expanded into an event that celebrated the growth of boys. During the period in which warriors were prominent, banners started to be adorned with designs of Musha-e (warrior pictures) featuring warriors and battle, along with Zhong Kui (a god that vanquished evil, derived from ancient Chinese stories).

As the Edo period started and common citizens become the center of cultural activities, Koinobori (carp streamers) was born and became a common practice to decorate with these streamers, as the valiant efforts of koi (carp) swimming upstream were popular among the common people. It is said that the Boys’ Festival dolls were also popularized among the common people during the Edo period.

The staple sweets for Tango no Sekku—Chimaki and Kashiwa-mochi

The most popular foods that represent “Tango no Sekku” is Chimaki (rice cake wrapped in bamboo leaves) and Kashiwa-mochi (rice cake in oak leaf).

Chimaki has a longer history—it is said that rice powder kneaded and wrapped in cogon grass leaves was steamed or boiled for eating during the Nara period.

On the other hand, Kashiwa-mochi was born during the Edo period. It initially featured salty red bean paste at its center, but as sugar started to permeate the society at the latter half of the Edo period, the center of Kashiwa-mochi started to feature sweet red bean paste and miso paste.

“Because the ingredients used for a dish may differ according to its period in time, in all likelihood, we cannot say that the food now is the same as the food with the same name a long time ago. The taste of the food in olden times will probably not be seen by modern man as delicacies,” says Okubo.

Various traditional Tango no Sekku dishes from around Japan

According to Toto Saijiki, documents that record the annual events in Edo, both Chimaki and Kashiwa-mochi were enjoyed during “Tango no Sekku” in Edo City (present-day Tokyo).

Generally, the Kansai region tends to make more Chimaki than Kashiwa-mochi, and Kanto region and areas to the north tend to make Kashiwa-mochi more than Chimaki. However, it is common for regions in which oak leaves cannot be harvested to use substitutes such as Sankirai (or Smilax glabra, a type of sarsaparilla), or leaves from bamboo, Japanese ginger, magnolia and tung trees.

“The word Kashiwa-mochi is commonly known, but there is a story behind this name as well. In ancient times, oak leaves were used as dishes, and kashiwa was the general word for dishes. An interesting fact is throughout history people settle on only certain types of edible leaves to use. For instance, cherry blossom leaves and hydrangea leaves are similar, but although we have cherry blossom rice cakes, hydrangea leaves are not used for food. It is said that hydrangea leaves are poisonous. The wisdom of our ancestors never fails to surprise me,” explains Okubo.

There are many different types of rice cakes and dumplings across Japan, and there is a variety seen as “Tango no Sekku”sweets as well.

Sasadango of Niigata

In Niigata, Sasadango, which are dumplings in bamboo leaves instead of oak leaves, are a local treat. Bamboo leaves are said to prevent dryness and to help preserve food, and had been used as wrapping for preserved foods and portable meals since ancient times.

These days this sweet is popular as a local souvenir, but according to historical documents on the Nagaoka territory of Echigo Province, Chimaki and Sasamochi had been used as “Tango no Sekku” gifts during the Edo period, and in the Nagaoka region, these triangular Chimaki and Sasadango are still staples for “Tango no Sekku” sweets.

Akumaki of Kagoshima

In Kagoshima, there is no custom of eating Kashiwa-mochi at “Tango no Sekku”. Instead, a Chimaki called Akumaki, which is wrapped in bamboo bark, has been the local sweet from a long time ago.

As this delicacy is simmered in lye (aku), it is caramel-colored inside, and the rice cake has a distinct sulfur-like scent. It is eaten with soybean flour or brown sugar syrup, and is one of the most famous sweets of Kagoshima.

Additionally, not only sweets, but many “seasonal” products of the regions’ sea and mountains are also seen in local dishes for “Tango no Sekku”. Getting to know seasonal festival dishes is one way to learn about local culture and history.

“The distribution structure of food has changed these days, and the unique food culture in each locality has started to fade. We might as well eat what we want, because it makes no sense having seasonal festival foods without any knowledge of its cultural history. I am not saying that there is a right and wrong way about this, I just believe that it is important to make choices based on knowledge on why a particular type of food is eaten,” said Okubo.

Seasonal festival food has each evolved in its own special way according to its locality. How about having a seasonal festival feast for this upcoming ”Tango no Sekku”, with food that has been traditionally handed down in your region?