Six Local Summer Sweets Bring Coolness

Local summer sweets, steeped in the wisdom of our ancestors.

Local sweets have weaved their food culture along with the history of their region. During times when preservation and logistics were less advanced than they are now, seasonal local sweets made from special products were strongly connected to the four seasons. Among them, cold sweets are essential for braving the hot summer months.

Local sweets have been adapted in various ways and remain popular today. This means that they are constantly evolving. Here are six local sweets that are perfect for summer.

Kuzumochi(Nara Prefecture)

Kuzumochi is widely enjoyed throughout Nara Prefecture. Its translucent appearance looks cool, and its plump texture is irresistible. Its ingredient, kudzu, is a perennial plant of the legume family and is widely distributed throughout Japan, from Hokkaido in the north to Kyushu in the south. Its name is thought to have its roots in the production of kudzu powder by the Kuzu people, a mountain tribe who inhabited the Yoshino region of Nara Prefecture.

Making kudzu powder is a laborious process that involves repeatedly refining the starch in the kudzu root using underground water. After this, the powder undergoes a drying process lasting two to three months. The powder, made purely from kudzu starch, is called Yoshino honkuzu. The traditional process of Yoshino zarashi, dating back to the Edo period (1603-1868), is still used today.

Kuzumochi is available locally all year round and is eaten with roasted soybean flour or brown sugar syrup added to taste. You can also get creative by trying it with ice cream, shaved ice, or in a kuzu zenzai, a sweet adzuki bean soup with kudzu. When freshly made, it is blanched in ice water just enough to leave it slightly warm inside, which gives it a sticky, soft mouthfeel.

Kanzarashi(Nagasaki Prefecture)

Kanzarashi is a traditional local sweet of Shimabara, Nagasaki Prefecture. Rice flour dumplings are cooled in spring water and eaten with sugar or syrup. It is still eaten at home but its taste varies due to the simplicity of its recipe. Various styles of kanzarashi can enjoyed in restaurants in the city.

Kanzarashi was born out of the wisdom of the people of Shimabara, who were common folk who had to pay tax in the form of rice. As their staple food, they consumed broken rice, which was stored as rice flour. However, this flour would spoil during summer. So, they devised the idea of making dumplings from rice flour and preserving them in spring water.

The popularity of this product was also spurred by the abundance of groundwater resulting from the Unzen landslide and tsunami in 1792. Furthermore, the syrup was made using sugar, a specialty of the Shimabara area. Eventually, the custom of entertaining summer guests with rice-flour dumplings dipped in syrup arose, and the prototype of kanzarashi took shape. The name kanzarashi is said to derive from a phrase meaning “exposed to the cold,” coming from the fact that rice flour was made around the coldest day in winter.

Shirokuma(Kagoshima Prefecture)

The Kagoshima specialty shirokuma is a type of shaved ice. The basic style is to pour condensed milk over shaved ice and top it with cherries, raisins, mandarin oranges, pineapple, azuki beans, and agar-agar. According to a widely held view, this dessert has its roots in a restaurant established during the 1950s. However, when it was first sold, it only consisted of shaved ice covered with white and red syrup. Improvements such as pouring condensed milk-flavored syrup and garnishing with colorful fruits were later made. Its unusual name, literally meaning “polar bear,” is attributed to the dish with toppings resembling such a bear’s face when viewed from above.

At a time when a typical bowl of shaved ice was about 20 yen, a shirokuma was a luxury dish costing 50 yen. However, it has become a summer tradition that can be enjoyed casually. It has been adapted in various ways, including chocolate-covered and pudding-topped shirokuma.

Warabi mochi(Nara Prefecture)

Warabi mochi is a Japanese confectionery made of bracken flour. It is made by heating a mixture of bracken flour, water, and sugar, then cooling it to set. Warabi mochi is a specialty of Nara Prefecture and is often eaten from spring to summer. It has a long history, so much so that in 1709, a visitor to the Great Buddha Hall of Todaiji Temple wrote in his pilgrimage diary that “there are so many tea houses specializing in warabi mochi in front of the temple.”

So, why has warabi mochi become Nara Prefecture’s specialty? The following legend survives in the Kasugano-cho district of the city of Nara. Once upon a time, it was believed that setting mountains ablaze would drive away the specters emanating from the Uguisuzuka tumulus at the top of Mt. Wakakusa. Arson by those who feared the superstition continued unabated, and the threat extended to the Todaiji Temple precincts and neighboring temples.

When the No Arson signs failed to work, Todaiji Temple, Kofukuji Temple, and the Nara Magistrate’s Office colluded to prevent such fires. The residents burned the mountain to prevent arson while the three parties were present. This action led to the growth of bracken in the burnt area, which eventually became a hub for producing bracken flour. Warabi mochi is currently made using this ingredient. Today, the burning of the mountain is a traditional early spring event known as Wakakusa-yama-yaki.

Uji kintoki(Kyoto Prefecture)

Uji kintoki is shaved ice drizzled with Uji matcha syrup. It is a popular flavor commonly topped with ogura-an (chunky adzuki bean jam) and rice flour dumplings.

The Uji tea from which Uji matcha is one of Japan’s most prized teas. According to legend, in 1191, a Zen monk named Eisai brought tea seeds from Song, and the plant was cultivated in Toga-no-o, Ukyo-ku, Kyoto by Buddhist monk Myoe. Tea cultivation was encouraged in the Muromachi period (1336-1573), and tea plantations developed in Uji. From there, the custom of drinking tea flourished, and Uji tea, grown in the area, became a highly valued product often given as a gift.

Additionally, Chanoyu, which involves admiring room décor and tea utensils, became popular among the general population. During the middle of the Edo period (1603-1868), Nagatani Soen created the Uji method, which involved a distinctive manual tea kneading technique. The method became popular in Edo and gained recognition throughout the country. Currently, the primary production areas are Uji and the Yamashiro region in southern Kyoto Prefecture.

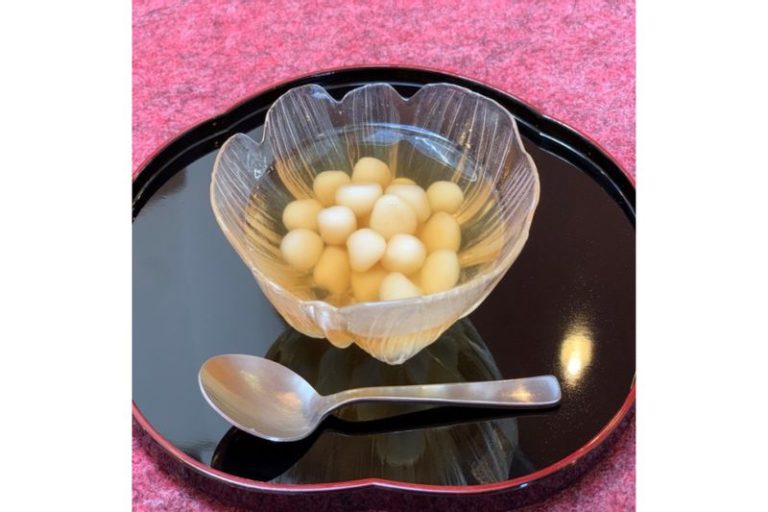

Mizumanju(Gifu Prefecture)

Ogaki in Gifu Prefecture is home to 15 class A rivers. Mizumanju is a Japanese confectionery that heralds the arrival of summer in this city, which is also known as the “city of waterways.” It is a refreshing and cool dish made with kudzu powder and bracken flour paste. This paste is used to wrap sweet adzuki bean jam. The traditional custom is to cool the mizumanju in a sake cup with groundwater.

In the Meiji era (1868-1912), people were already enjoying mizumanju. During this time, households used troughs to store groundwater, which functioned as refrigerators as we know them today. Mizumanju is believed to have originated as a cold snack that utilized this storage method.

When it was first created, the main ingredient was only kudzu powder, butit is easily soluble in water and hardens when cooled. As a solution, bracken flour was added to the mixture, which enabled the paste to stay firm even when cooled.

In Ogaki, mizumanju is available from April through September in confectionery stores. Mizumanju submerged in water at the store are cool and smoothly glide down the throat.

Summer local sweets are diverse, ranging from kuzumochi, with its addictive plump texture, to shirokuma, with its eye-catching presentation. Their cool, refreshing taste is a summer luxury that has endured through the ages. A closer look at the background of their creation reveals the local culture and the wisdom of ordinary folk.

Written based on the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries website Uchi No Kyodo Ryori (Regional Home Cooking).