Oyama’s Tofu Cuisine, Nurtured by Mt. Oyama’s Clear Spring Water

Oyama tofu, an essential part of the Oyama Pilgrimage experience

On the eastern side of the Tanzawa Mountains, Mt. Oyama straddles the cities of Isehara, Hadano and Atsugi. The beautiful pyramidal mountain, 1,252 meters above sea level, has been the object of mountain worship since ancient times. This mountain is traditionally called Afurisan because it is believed to have the power to make rain. Afuri Shrine’s headquarters sits on the summit of the mountain as if watching over the entire area.

In the Edo period, the Oyama Pilgrimage became trendy in the Kanto region and was enjoyed as a form of leisure. At a time when the population of Edo was one million, 200,000 pilgrims a year visited the mountain. It became fashionable for commoners to make pilgrimages to Mt. Oyama and Mt. Fuji. Many believed that if you climbed one mountain, you had to climb the other.

The Isehara Station in Isehara serves as the entryway to Oyama. After exiting the North Exit ticket gates, one can see the Afuri Shrine’s otorii (Grand Gate). Despite its mighty presence, it blends in with the streetscape without any sense of incongruity. The shrine town’s character has been preserved.

The local specialty, Oyama tofu, also owes its origin to the Oyama Pilgrimage. It took root in the region due to a combination of conditions: soybeans devoted by pilgrims mainly came to Oyama, monks used tofu in their Buddhist cuisine, and the region’s spring water was ideal for tofu production.

In the old days, pilgrims walked along the path to the shrine while slurping tofu in their hands. In the summer heat, tofu cooled by spring water must have tasted especially refreshing.

Oyama tofu has become a tourist resource, and the Oyama Tofu Festival is held in the Oyama district in late March every year. The two-day event is devoted to tofu, starting with a Sennin Nabe serving 1,000 portions of boiled tofu, followed by a tofu-themed panel discussion, live performances, and more.

Koide Tofuten's excellent tofu is loved by people of all generations

Oyama tofu is the generic name for all tofu produced in the Oyama area. Since no detailed rules regarding production methods or ingredients exist, each manufacturer pursues its unique flavor.

Koide Tofuten, established in 1883, is one such store. About a 20-minute drive from Isehara Station, the store suddenly appears in the basin of the Suzu River along a prefectural road lush with greenery.

“We make tofu with water drawn from Mt. Oyama. Since tofu is mostly made of water, it wouldn’t taste like it does without this spring water. It’s rare nowadays, but I think this style was common before running water became widely available.”

So says Takayoshi Kato, the store’s fourth-generation owner. The store was originally based in Odawara, but his great-grandfather, anticipating the demand from pilgrims, decided to relocate to the Oyama district.

The millstone used for grinding soybeans has been replaced by a fully automatic grinder, and the wood-fired kettle used to boil the squeezed juice from the soybeans has been replaced by a boiler. Although some processes have been mechanized, the basic production methods have not changed since the store’s establishment. The kettles are fired up at 2:30 a.m. for the 8:00 a.m. opening.

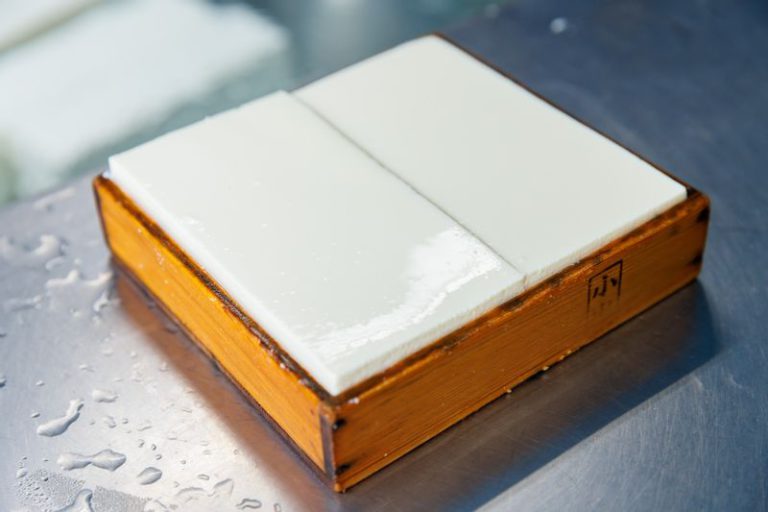

Kato explains, “Once the soy milk is poured into the mold and allowed to coagulate, it is exposed to running water for a while. I don’t think we’re doing anything special, just adhering to the traditional production method. I rely heavily on experience and intuition and pay particular attention to the “yose” process of stirring soy milk when it coagulates. If I don’t do it right, the flavor will be inconsistent, so I must be careful.”

What is the difference between his tofu and the ones found in supermarkets? To this question, Kato treated us to silken tofu as if to say, “You’ll see when you try it.”

The first thing that surprised me was its bounce. It could be easily lifted without falling apart when picked up with chopsticks. Yet, it is smooth on the palate. It is light, so it can be used in various dishes.

“When I eat it chilled, I often drizzle olive oil over it. My wife recommends mapo tofu. It’s delicious enough, even if you just use store-bought mapo tofu sauce,” comments Kato.

The painstakingly made tofu is sold directly at the store and wholesale to nearby inns and restaurants. It is also served in school lunches at primary schools and is now enjoyed by people of all ages. However, only two tofu stores are currently in the Oyama district, including Koide Tofuten. The culture of Oyama tofu, originating from mountain worship, is only barely kept alive in the local community.

Kato comments, “I wasn’t well for a while and had to take a break. At the time, I thought that physically it was time to retire. But I received a letter of encouragement from a regular customer. Their thoughts inspired me to keep going. Now I want to keep the store open as long as possible.”

A tofu restaurant with its roots in an Edo period shukubo

As one continues along the prefectural road from Koide Tofuten, the road joins Koma Sando, lined with souvenir stores and shukubo. Shukubo refers to lodging houses for pilgrims on their Oyama Pilgrimage. In the days when roads were less developed than they are today, the innkeepers acted as guides to lead pilgrims on the steep trail to the mountaintop. This custom continues today, with guides assisting visitors during major events.

As you come to the end of the approach, you will see a magnificent gate. The signboard reads Tofu Dokoro Ogawaya. This is another tofu restaurant that has its roots in a lodging house. The owner, Yoshimi Ogawa, explains the restaurant’s origins as follows.

“Although historical documents were lost in the Great Kanto Earthquake, our place is believed to have been founded in the early Edo period. Originally, we ran a lodging house, but in the 1970s, we shifted to the restaurant business. At that time, the number of pilgrims was starting to increase, and we wondered if we could offer our famous Oyama tofu.”

Ogawaya offers a wide variety of tofu dishes as set menus. The seven-course menu they prepared for us that day was an impressively extensive array, including a shira-ae made with mashed tofu combined with spinach, tofu gratin, and a dessert made with tofu and soymilk.

Ogawa explains, “We use silken tofu from Koide Tofuten for boiled, deep-fried, and steamed tofu. The key is to make the most of its smooth texture. This selection is just a small sample, and we change the menus seasonally.”

He and his son have been developing menus that appeal to young people. Besides tofu-based dishes, the entire community is also exploring the use of wild game.

“As a healthy food, tofu is well-known by visitors to Japan. It would be great if the customs and culture rooted in this region could be widely known through Oyama tofu,” says Ogawa.

Oyama tofu was born out of peculiar circumstances and nurtured by the famous water. The one-of-a-kind flavor of this unique product is a testament to the integrity of its creators, who have continued to protect it.