Enjoying Go-sekku (Five Seasonal Festivals): July 7, Shichiseki no Sekku

For this article, we visited Hiroko Okubo, one of the board members of the Washoku Association of Japan, and asked her about how Shichiseki no Sekku spread throughout Japan, and how the seasonal events were celebrated over time.

A unique event featuring fables and customs from both China and Japan

Shichiseki no Sekku is one of the Go-sekku, but it stands out from the others because of how it came to be—it is a combination of Chinese star festival legends, and faith toward the old water gods and the Obon (festival for honoring the spirits of deceased ancestors) culture of Japan,” explains Okubo.

Go-sekku is based on yin and yang philosophies and derived from traditional Chinese events that deemed a combination of odd number days to be unlucky. As these customs were carried over to Japan, it spread as a celebratory event to be held at the changing of the seasons as time went on.

However, the July 7 Shichiseki no Sekku was also popular in China as a day related to the old Star Festival legend in which a herdsman (the star Altair) and a weaver (the star Vega) are allowed to meet only once a year on this day.

Furthermore, an event called Kikkōden was also held. This event had people praying for further skills in music and calligraphy, and also sewing and weaving, which came from the weaver in the legend.

It is said that Kikkōden and the Star Festival came over from China to Japan in the Nara period (710–794), and was combined with the existing religious services the Japanese held toward the water god at that time.

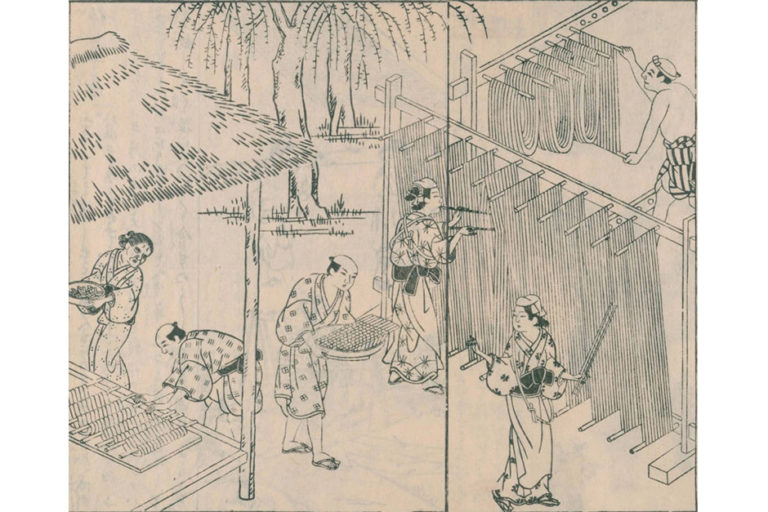

In the imperial court of ancient Japan, garments were a signature of one’s social position. This is why jobs related to clothing, especially weaving, were regarded as extremely important. Weaving was noted as a woman’s job in the past, and it is said that weavers called Tanabatatsume would stay in shacks on the waterfront, and performed ceremonies praying to the gods for improved weaving skills.

“Although there are many theories, it is said that the common aspect of a female weaver linked the Chinese Star Festival and Tanabatatsume, resulting in the characters of Shichiseki to be read as “Tanabata.” The original kanji characters cannot be read as “Tanabata” at all, no matter what combination of readings are used.”

The Kikkōden event in the imperial court became the Tanabata Festival for commoners

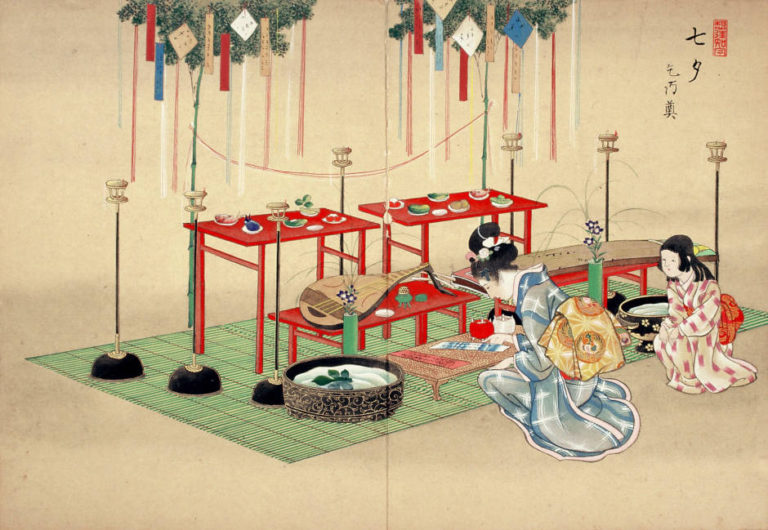

When Shichiseki no Sekku was initially introduced to Japan, aristocrats had been holding Kikkōden as an imperial court event. An alter called Hoshi no Za (star constellation) was constructed and decorated in yarn in five colors, mulberry leaves, Japanese koto and biwa instruments. Prayers to improve artistic skills were made, based on the Weaver.

“As aristocrats attached importance to having excellent penmanship, it is said that wishes for better penmanship were written on mulberry leaves in the form of Japanese poetry. A custom was born in the Muromachi period (1336–1573) in which people would use the dew from taro plant leaves to grind ink on their ink stones, wishing for better penmanship,” says Okubo.

It was not until the Edo period (1603–1868) that Tanabata spread to the commoners, allowing them to start the custom of decorating bamboo with small pieces of paper.

Children of commoners started to learn their “reading, writing and arithmetic” at temple schools during the Edo period. Having good handwriting meant better work positions for boys, and was also an attractive feature for girls. Therefore, much focus was put on practicing penmanship. According to Okubo, as a result of this environment, commoners started to write their wishes of better artistic skills and studies for their children on small pieces of paper.

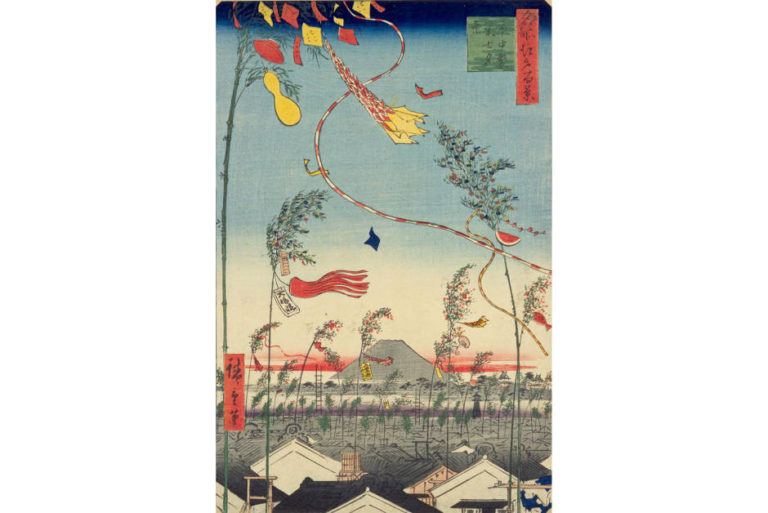

It was said that the taller the bamboo stalks were, the better they were for decorations, and green bamboo leaves were tied on to tips of moso bamboo stalks. As commoners in this era did not have gardens, these bamboo stalks, decorated with colorful streamers and paper pieces, were erected on the rooftops of houses in town.

The Tanabata decorations can be seen flying above Edo houses in pictures documenting customs during that time.

It is said that these colorful Tanabata decorations, which livened up the Edo town, were completely removed by the night of Tanabata, and sent down a river to make these prayers come true.

“Hints of the Tanabatatsume, which was a sacred ceremony to the water god, can be seen in this ritual of sending the decorations downstream. Because many areas prohibit floating items in rivers now, the custom of sending Tanabata decorations downstream has become obsolete. Moreover, since it has become more difficult to discard tall bamboo stalks, Tanabata decorations for each household are gradually becoming smaller.”

By the way, how did bamboo stalks and leaves come to be used for Tanabata?

“In the imperial court, Tanabata flowers were called Nadeshiko. However, Nadeshiko was recognized as one of the seven autumn flowers among the common people, so it did not catch on as a Tanabata flower. Meanwhile, bamboo stalks and leaves were regarded as good luck because of the rapid speed in which bamboo grows. The common people were very fond of bamboo, and it may be because of this that bamboo was used as a receptacle for their prayers and wishes.”

Although Tanabata was immensely popular among townspeople during the Edo period, the tradition was discontinued temporarily after the Go-sekku holidays were abolished in 1873.

The custom returned after World War II, as commercialization progressed and shopping districts attempted to outdo each other with gaudy Tanabata decorations to bring in customers. As the center of commercialization moved from shopping districts to city outskirts, the Tanabata festival disappeared from many shopping districts. However, some large-scaled Tanabata festivals can still be seen in Sendai, Miyagi Prefecture, or Hiratsuka, Kanagawa Prefecture. Many tourists flock to see the Tanabata decorations at these colorful festivals.

The dish for Shichiseki no Sekku: Somen noodles

Karakudamono (deep-fried Chinese pastries) called sakubei (or muginawa) are believed to be the origin of somen noodles

It is said that the imperial courts during the Heian period (794–1185) enjoyed deep-fried flour dough, twisted into ropes, called sakubei. This dish was also called muginawa in Japan, and is a deep-fried pastry brought over from China. The pastries during that time did not use any sugar and were not sweet at all. Nowadays, this pastry has changed its recipe to one that is more palatable and sold as a variation of karinto (fried dough cookies) in the same traditional rope shape.

“It is believed that the methods of eating this dish changed along the way—during the process of making sakubei, the kneaded flour was pulled more and more, and steamed instead of deep-frying. At the latter half of the Muromachi period, somen as we know it in modern times was created. Some documents state the name as sakumen, and it is thought that the name transitioned from sakubei to sakumen to somen.”

Okubo states that the progress of flour milling technologies contributed greatly to the popularization of the somen culture.

“During the Heian period, flour was milled in small hand mills like those used to grind tea leaves. Due to this, foods using flour were a luxury item, and limited only to people of a high social status. Yet, in the Edo period, the popularization of water mills allowed flour milling technology to develop, and flour foods such as udon, somen and soba noodles became popular. Udon is made from pulled dough that is cut thinly, but somen is created by pulling dough into thin noodles, not by cutting it.”

Another reason somen is believed to be eaten on Tanabata is that it replaced the five-colored yarns that were offered at events that took place at the imperial court.

“It is believed that the similar-looking somen was offered in place of colored yarn, which was a luxury item for commoners.”

In the Toto Saijiki (Customs of the Eastern Capital), there is an entry about “Tanabata entertainment with chilled sakumen (chilled somen)”, and it is believed that eating somen on Tanabata had become a custom amongst the Edo townspeople.

There are other dishes using seasonal ingredients for offerings at the other Go-sekku events, such as alcoholic beverages or mochi (rice dumplings), but none of these customs apply to Tanabata. It may be because the time of year around Tanabata is before rice harvest, and susceptible toward rice shortages.

It is said that seasonal dishes in each region were used for offering instead at Tanabata. According to Shokoku Fuzoku Toijo Kotae (Answers to the questions on customs of all areas) (circa 1815–1816), it was standard practice to offer gourds or watermelons for Tanabata in Edo.

“In some areas, it seems that there were areas where cucumbers and eggplants were offered. Cucumbers and eggplants now have a strong image of offering Obon, but the Tanabata of the lunar calendar may overlap with the Obon season. In the private sector, it is believed that the cultures of Tanabata and Obon were mixed. “

There are entries stating “gifting somen at Tanabata as Obon gift” in the Shinmotsu Benran (gift-giving handbook) (1811), and the connection between Tanabata and Obon can also be seen here. This custom is believed to be related to the ochugen (summer gift giving) culture in modern Japan.

The Tanabata culture was born from a mixture of various customs. The star legend is the most popular aspect of this festival in nowadays, but it has been a special day for wishes and prayers of the people for many years.

A corporation Miwa Yamamoto.

https://www.miwa-somen.jp/