Traditional Food “eel” for “Doyo no Ushi no Hi” for Surviving A Hot Summer

Prevent summer fatigue by eating foods with "u" on the summer Doyo no Ushi no Hi

Doyo no Ushi no Hi falls in the middle of the hot summer season. There remains an ancient custom on this day of eating eels to nourish the body. Yet, not many people have ever been aware of its origins. By definition, Doyo refers to the approximately 18 days immediately preceding Risshun (the first day of spring), Rikka (the first day of summer), Risshu (the first day of autumn) and Ritto (the first day of winter). In other words, it means the change of the season. Based on the ancient Chinese theory of Yin-Yang and the Five Elements, the five elements comprising all things, the “earth” (Do) element, is applied to the 18 days of the year.

Ushi no Hi derives from the Ox in the 12 Chinese zodiac signs. The 18 days of Doyo are divided into Rat, Ox, Tiger, Rabbit, Dragon, Snake, and so on in a 12-day cycle, and the day that falls exactly on the Ox is Ushi no Hi. Consequently, depending on the year, Doyo no Ushi no Hi comes twice.

Eels are now considered a special food for the Doyo no Ushi no Hi, but legend has it that eating any food starting with the character “u” would prevent summer fatigue. For example, pickled plums improve loss of appetite and quench thirst. In addition, our predecessors braved the hot summer months by eating melon, which releases body heat, and udon, which is easy to digest. There was also the custom of eating dark foods such as basket clams, loaches, and burdock roots. These were in reference to the black color symbolizing Genbu, the sacred beast that governs the direction of the Ox (North).

There are also legends concerning other Doyo; the spring Doyo, the autumn Doyo, and the winter Doyo, during which foods with the characters “i,” “ta,” and “hi” were eaten, respectively.

Doyo no Ushi no Hi was contrived by Hiraga Gennai, a polymath of the Edo period (1603–1867)

The benefits of eels have been known since ancient times, and Manyoshu (the Anthology of Myriad Leaves), compiled in the Nara period (710–794), contains waka poems describing this fact.

“Ishimaro ni ware mosu—Natsuyase ni yoshi to iu mono so unagi tori mese” (Otomo no Yokamochi, Manyoshu Vol. 16, verse 3853)

The above poem is saying to Ishimaro to catch eels and eat them because they are good for him if he is losing weight in the summer. The name kabayaki (broiled eel) was coined even further back in time, at the end of the Muromachi period (1336–1573). In those days, eels were prepared with great gusto, chopped into chunks, and grilled on skewers. There are various theories, but the name kabayaki is believed to derive from its shape, which resembles gamano-ho, the ears of cattails.

There is a prevailing theory that the custom of eating eels on the Doyo no Ushi no Hi began in the Edo period. The man who engineered this was Hiraga Gennai, a scholar of Dutch studies in the mid-Edo period. When Hiraga heard the woes of an eel restaurant, “We need to do something about the sluggish summer business…,” he exercised his talent as a producer. He launched what is now called a promotional campaign with the catchphrase, “Today is the Doyo no Ushi no Hi.”

Did the trend-conscious Edo people really jump on the eel bandwagon? Dr. Hiroko Okubo, the author of a book on Edo’s food culture, analyzes, “They were probably not as enthused as people are today.”

“Nowadays, we treat ourselves to eels, but for the average Edo folks, eels were readily available and common. I don’t think they gave it special treatment just because it was the Doyo no Ushi no Hi,” says Dr. Okubo.

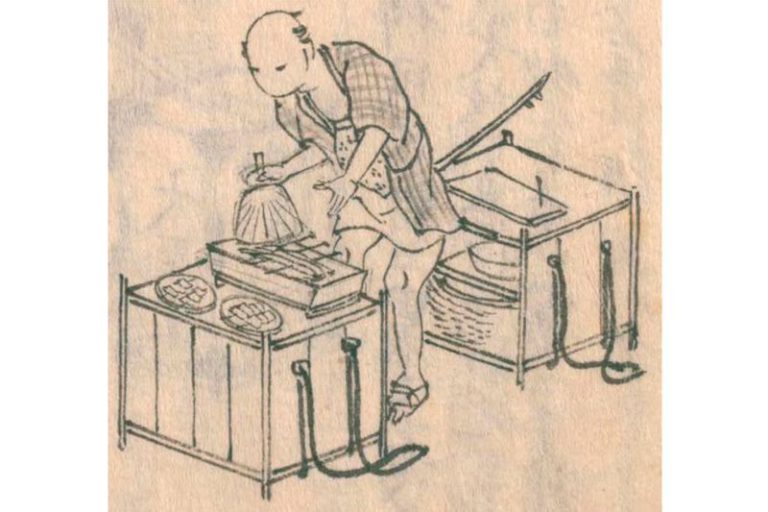

She attributes this to the culture of eating out that flourished during the Edo period. In the mid-eighteenth century, Edo had grown into a city with a population of more than one million people. Many single men lived in the city, and the custom of grazing between manual work to satisfy hunger took root. There was a concentration of eateries in areas where people congregated, like an amusement quarter. Among them were street hawkers selling kabayaki and eel restaurants.

“Since the samurai were distinct from the life of the lower classes, eating out on the street was a small pleasure reserved for ordinary folks. Tempura and sushi cost four mon each, which is about 100 yen in today’s terms. The kabayaki was a little dearer as it was eight mon. At that time, many eels were caught in Edo, and ‘Edomae’ meant kabayaki. Fukagawa and Tamagawa (Tama River) eels were especially prized,” says Dr. Okubo.

The Edo period was also when food culture flourished among the general populace. The Osaka style of preparing eels, known as hara-biraki (opening the belly), was replaced in Edo by se-biraki (opening the back), influenced by samurai warriors who disliked the idea of slicing open the belly. Eventually, as soy sauce and sugar production technology developed, the rivalry among stores intensified in earnest. From a lighter soy sauce-based seasoning, a sweet and salty sauce was used, refining the taste to something closer to what we have today.

Dr. Okubo says, “There was no television or the internet, unlike today. Cooking methods and production techniques were circulated orally, and over some 260 years, they must have taken root in people’s daily lives. Even though there was no scientific basis for the benefits of eels, they must have been naturally accepted as the wisdom of their ancestors.”

However, once readily available, the catch of eels has declined since the 1970s, and prices have continued to soar. Dr. Okubo expresses concern that “we may not be able to eat eels in the future.”

She says, “Food culture is something born out of everyday life. It is a little unfortunate that the Doyo no Ushi no Hi has been reduced to a mere event. I hope that people today can follow the example of the Edo people and protect eels by selling and eating them with moderation.”

Long-established eel restaurant named in Edo's famous restaurant rankings

Peace without major warfare prevailed during the Edo period. Once a means of survival, food eventually became a luxury and a pleasure in itself. The number of so-called “gourmets” who expounded their knowledge of food stalls and restaurants increased.

In 1852, the Edomae Dai Kabayaki Banzuke was published, the equivalent of today’s restaurant guide. It rates over 200 eel restaurants in Edo in a ranking system.

Among the best restaurants ranked on the list include old establishments still in business. Komagata Maekawa, in Asakusa, Tokyo, is one such restaurant. About 220 years ago, the river fish wholesaler Ohashi Yuemon changed his business to an eel restaurant. Currently, the restaurant is at the foot of Komagata Bridge over the Sumida River.

“Many of our customers are families that have been loyal to us for generations. Since the opening of the Tokyo Skytree® and the Tokyo Solamachi commercial complex, we have been seeing an increase in the number of young people visiting us. The restaurant gets so busy on the day of the Sumidagawa Fireworks Festival that people make reservations a year in advance,” says the owner.

The owner, Kazuhito Ohashi, is the restaurant’s seventh successor. To preserve the traditional flavor he inherited at a young age, he works actively on branding, such as opening a store in a station building and operating an e-commerce site.

On the day we visited, Ohashi served an unaju (broiled eel served on rice in a rectangular serving box) using Bando Taro, a farmed eel brand from Chiba Prefecture. The thick kabayaki on rice is Kanto style, prepared by the process of broiling with salt, steaming, and grilling. It has just the right amount of fat and pairs well with the light sauce.

“We use only soy sauce and mirin for the sauce. We add more every day to the sauce, which has survived World War II. Since it does not contain sugar or syrup, it has a clean, light texture. It is relatively salty, but when it melds with the sweetness of the eel fat, it strikes a perfect balance. Please compare it with the shirayaki (broiled eel seasoned with salt),” says Ohashi.

Komagata Maekawa’s menus also include Spanish wines. The restaurant breaks new ground in eel cuisine by recommending pairing red wine with kabayaki and white wine with shirayaki.

Doyo no Ushi no Hi in 2022 falls on July 23 and August 4. We invite you to reflect on the ancient food culture by enjoying eel dishes and other foods prefixed with “u.”