Wishing for Children’s Growth with Shichi-Go-San’s Chitose-ame

Milestone celebrations for commemorating children’s growth gave birth to Shichi-Go-San

We asked food-culture scholar Hiroko Okubo how the Shichi-Go-San event spread throughout Japan and the historical background on how we came to eat chitose-ame.

“It was hard for children to thrive in the olden days. There were many stillbirths, and since a lot of them did not survive infancy, we had many events for celebrating children’s growth at every milestone,” says Okubo.

The Shichi-Go-San festival for celebrating children’s growth at ages three, five and seven was originally three separate events: Kamioki, Hakamagi, and Obitoki.

“We do not know exactly when each of these events began, but the oldest recorded event refers to the ceremony of Chakko, an ancient name for Hakamagi, practiced among court nobles in the Heian period.”

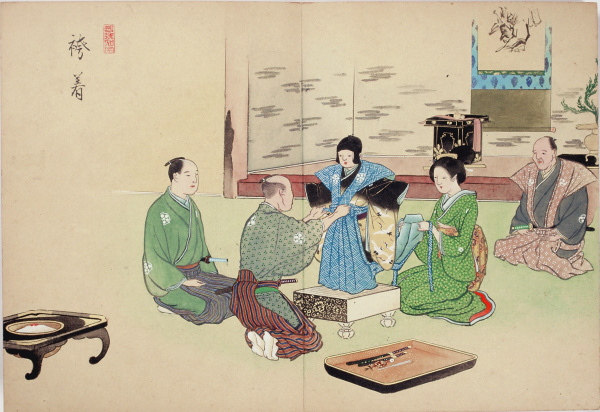

Hakamagi was a ceremony for fitting a five-year-old child with his or her first hakama (trousers). According to Heian period (794–1185) documents, it was celebrated on an auspicious day divined by a yin-yang master, and each family chose its lucky day to enjoy a magnificent celebration.

A record of the Kamioki ceremony to mark age three is found as the ceremony of Seihatsu in Azumakagami, a book of history from the Kamakura period (1185 – 1333). In those days, children had their heads shaved until they were three, and the ritual marked the occasion for them to start growing their hair.

It is believed that the ceremony of Obitoki, fitting a child with their first obi (sash), began in the Muromachi period (1336 – 1573). It was a milestone for a child to remove their garment made for children, which had ties to make it easy to wear, and don a kimono with a proper obi like adults. It is regarded as a ceremony for seven-year-olds today, but it was often celebrated at age nine in the past.

“All of these ceremonies were originally held regardless of gender, and there were no particular dates set for them,” says Okubo.

The Shichi-Go-San celebrations spread among the common people of Edo

Thus, the ceremonies that began among court nobles spread among the warrior class during an era governed by them. It was not until the Edo period (1603 – 1868) that Shichi-Go-San began to appear in the records of the common people of Edo.

“It appears that the Shichi-Go-San celebrations were practiced among the common people, primarily in urban areas, in the Edo period. It is also likely that the festivities for ages three, five and seven became collectively called Shichi-Go-San and established as a festival held on November 15 in the Edo period.”

As Japan enjoyed a time of peace in the Edo period, merchants rose as the affluent class even though their social status was low. It is said that in the mid-Edo period, wealthy merchants began to spend money on kimonos.

“Costumes for visiting the shrines and temples for the Shichi-Go-San celebration gradually became more elaborate, and not just the children but their mothers and servants paraded around in gorgeous outfits. The scenes looked like fashion shows.”

Against the exceedingly glitzy attire, however, the Edo shogunate issued sumptuary laws. People gradually abandoned the practice of visiting the shrines and temples for Shichi-Go-San after restrictions were placed on their clothing. Each family and community began to commemorate children’s growth in ways not bound by the Shichi-Go-San tradition.

“It was not until after World War II, when people became financially stable, that Shichi-Go-San made a comeback as an event. It was then that Hakamagi became a ceremony for boys as boys wore hakama. The age seven celebration became one for girls as girls wore obi. And the age three celebration became one for both boys and girls as three years old is still young,” commented Okubo.

Chitose-ame derived from Edo’s hit product, ame

Chitose-ame probably comes to mind when we think about food associated with Shichi-Go-San. There are various hypotheses as to the origins of chitose-ame, but it was evidently the brainchild of an Edo candy merchant. Candy merchants were highly sought-after by children in the Edo period (1603 – 1868) and they had stalls along thoroughfares and shrine grounds.

“The common people were able to enjoy sweets at a time when sugar was precious because candies in Japan at that time were made of saccharified malt, which we call mizu-ame (starch syrup) today.”

Mizu-ame has a long history, and it is said that people began eating it from around the Nara (710 – 794) and Heian (794 – 1185) periods and that it was also used as medicine.

Talented candy merchants of Edo began selling their wares, giving them names associated with longevity such as jumyo-to (longevity candy), sennen-ame (thousand-year candy) and senzai-ame (thousand-year candy).

According to one theory, it all began when Jinzaemon Hirano from Osaka began selling senzai-ame on the Asakusa Temple grounds while visiting Edo on business. The sweet became popular as a candy that promotes longevity. Its original name, senzai-ame, was changed to chitose-ame, written with the same kanji (Chinese characters) but pronounced differently.

Another theory claims that a candy merchant named Shichibei sold candy called sennen-ame or jumyo-to in Asakusa during the years of Genroku and Hoei (1688 – 1711), and it is mentioned in the 1826 essay “Kangon Shiryo” by Tanehiko Ryutei.

“When chitose-ame began selling, it was not just for children, although it may have become associated with Shichi-Go-San because children love candy,” says Okubo.

In the beginning, families celebrating the event would buy chitose-ame and share it with others. However, shrines started selling it on their grounds, and before long, people began buying it after visiting the shrines to pray.

The Shichi-Go-San celebration began to be held across Japan after the World War II, and chitose-ame also became widespread throughout Japan.

Chitose-ame transformed while keeping the tradition alive, and still lives on.

“The starch syrup used to make chitose-ame turns white as it traps air while it is kneaded and stretched. It also bulks up in volume and changes in texture. We get pink candy when we add red food dye.”

The basic measurement of chitose-ame is under 1 meter in length, with a diameter of 1.5 centimeters. It is not known when the candy took this form, but since an illustration in “Kangon Shiryo” shows a short, stick-like shape, perhaps today’s chitose-ame is different from how it looked initially.

“In general, the candy used to be simple with red and white coloring, but we now see ones with intricate motifs such as the kintaro-ame, as candy-making techniques have improved.”

It appears there was no specific food, apart from chitose-ame, that people ate for Shichi-Go-San.

People often enjoyed eating azuki (red bean) rice and fish, which were treats back in the day, for celebratory occasions not limited to Shichi-Go-San.

According to Shokoku Fuzoku Toijo-Kotae, a survey of the customs of various regions in late Edo (circa 1815 – 1816), a response by the Mito domain stated, “We often celebrate Kamioki, Hakamagi, Obitoki, and nuptials in November, so the price of fish increases,” indicating that fish was regularly served at celebrations.

Although the ways in which we celebrate and the ages of the children have changed, parents’ and society’s wishes for children’s growth have always been the underlying reason for the Shichi-Go-San celebration we have today.

Eitaro Sohompo

https://www.eitarosouhonpo.co.jp/

Kintaroame Honten

http://www.kintarou.co.jp/