Between the Summer Solstice and Hangesho—Special Dishes Honoring the Hard Work of Farmers

Summer Solstice: The Year's Longest Day

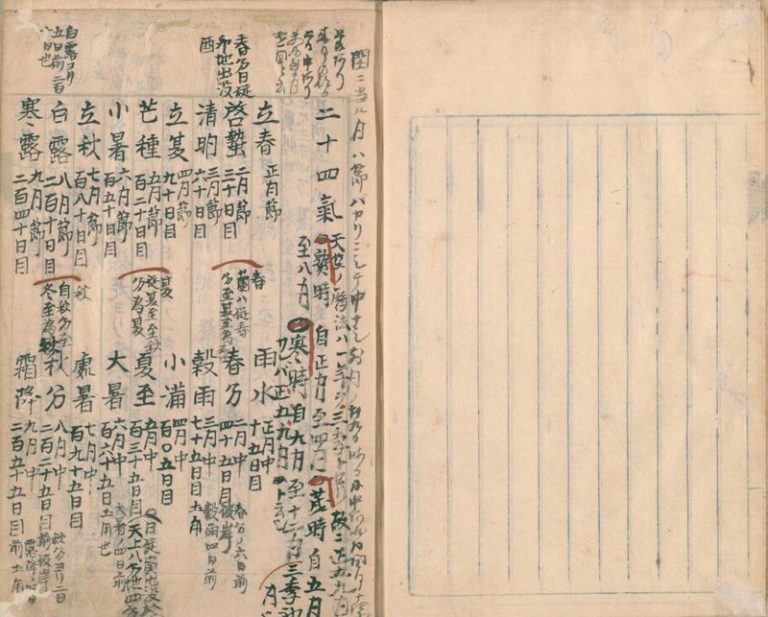

The summer solstice is the year’s longest day, falling annually on June 21. Based on the 24 solar term calendar that originated in ancient China, it is one of the 24 events marking the change of seasons within a solar year. Other events include Risshun on February 4, when the winter cold is said to subside and signify the coming of spring, and Shubun on September 22, when summer turns into autumn. The names of these events indicate the seasonal change that symbolizes the region’s climatic features.

The idea of dividing the year into 24 seasons is said to have been introduced to Japan in the Heian period (794–1185). Even today, we often see words describing the seasons in letters and newspaper pages. Having said that, it is a calendar that originated in China, so it doesn’t perfectly match the climate in Japan. Furthermore, with the influence of global warming and climate change in recent years, the climate differences between this traditional calendar and the real weather are only going to get more prominent.

Why There Are No Summer Solstice Traditions

However, despite the slight differences, traditional customs based on the 24 solar term calendar are still firmly rooted in Japanese people’s lives. There is even a Japanese calendar called “Zassetsu” that provides a simple explanation for the 24 seasons and includes names of events such as Setsubun (the day before spring begins), Higan (the spring and autumn equinoxes), and Doyo (the midsummer day of the ox).

It is believed that eating dishes that include the letter “n” in their name on the day of the winter solstice, which marks the start of cold winter days, brings good fortune. Stemming from this belief, a tradition of eating pumpkin, or nankin, on that day spread throughout the country. The custom supposedly goes back to the Edo period (1603-1868) when commoners began to eat pumpkins, praying for good luck in the coming year.

On the other hand, there are not many established customs associated with the summer solstice that are common across Japan. Both the summer and winter solstice signify the change of seasons, so why has this difference occurred? Kiyoshi tells us that the reason lies in the fact that the summer solstice coincides with the busy farming season.

“I’ve looked into this matter thoroughly, but I have yet to come across any traditional or special ceremonies related to the summer solstice. However, when you think about the original of the traditional 24 solar term calendar, it’s not really surprising. The summer solstice falls on the peak of the farming season, so they had no time to bother with festivities. Another issue was that there was no way to preserve food in the summer heat. That might be one of the reasons for the absence of elaborate, celebratory dishes.”

A Variety of Special Dishes Served across Japan to Celebrate Hangesho

Hangesho is a more significant milestone for farmers than the summer solstice. It refers to a period that begins on the 11th day after the summer solstice, around July 2 and lasts for five days until the Tanabata festival (July 7). There is an old saying “hange hansaku.” It means that if you plant rice after Hangesho, the crops in autumn will yield less harvest, and farmers back in the day would try their best to finish their work beforehand. There was even a legend explaining that poison would fall from the skies on Hangesho, so they must have been really pressed for time. When the day came around, the farm work would slow down, and they could finally get a good rest.

“The name ‘Hangesho’ is said to have come from a plant of the Araceae family called Pinellia ternata or Hange, which grows in the midsummer period. Since its flowers were in full bloom around the time of Hangesho, farmers must have viewed it as a sign to relax a little,” explains Kiyoshi.

Unlike during the summer solstice, the unique dishes eaten around Hangesho vary depending on the region. This traditional custom originated from the idea of thanking farmers for their hard work by eating nutritious food.

For example, in the Osaka Prefecture, which is where Kiyoshi was born, there is a tradition of eating octopus.

“As the time draws closer to Hangesho, octopus appears on the refrigerated shelves of supermarkets and fishmongers. At this time of year, their meat is tender and has an intense sweetness to it. It is commonly known as mugiwara-dako, or “straw octopus,” because it comes into the season after the wheat harvest. The culinary tradition of eating octopus during Hangesho seems to be mainly spread in rural areas. Apparently, people who live in such areas tend to eat this food, praying that the crop’s roots will firmly stretch into the ground like octopus tentacles,” says Kiyoshi.

Komugi dango, or wheat flour dumplings, are widely popular in the areas that grow wheat. As indicated by their name, the dumplings are made from wheat flour and characterized by a smooth mouthfeel and chewy texture.

“Komugi dango is a common staple in the prefectures of Gifu and Kochi. In some areas, they are named after Hangesho and called unique names like ‘hage dango’ or ‘hage manju,’” said Kiyoshi.

In terms of wheat flour, there is a traditional custom in Kagawa Prefecture of eating udon noodles on Hangesho, and July 2 is marked as “Udon Day.”

In Ono, Fukui Prefecture, there is a custom of eating whole grilled mackerel before the summer heat comes in. The origins of this tradition are not known for sure. However, there is a theory that one of the feudal lords many years ago recommended eating grilled mackerel to prevent summer fatigue and perhaps even distributed it among the people of his domain. According to historical records, it can be assumed that the custom of eating mackerel on Hangesho was popular, at least from the late Edo period.

“Fukui Prefecture is well-known for its mackerel being caught in Wakasa Bay. Although Ono City is located in the mountainous area, there are records of mackerel being supplied to a feudal domain from the Echizen coast.”

“There is also a customary treat that is known throughout the entire Fukui Prefecture. ‘Hobameshi’ is eaten during breaks from farm work. It is a rice ball wrapped in a hoba, or magnolia leaf, which seems to have been a popular, light snack.”

To celebrate Hangesho, a wide variety of regional foods are eaten. A few more are “akaneko mochi” in Osaka Prefecture and “kashiwa mochi” in Fukui Prefecture (Obama City and Wakasa Town).

Last but not least, minazuki, which is a Japanese confectionary customarily eaten in Kyoto Prefecture on June 30, the day of a “summer purification rite.”

The summer solstice and Hangesho are slowly becoming forgotten in modern life. However, according to Kiyoshi, “putting seasonal foods on the table is enough to feel closer to the old traditions.” How about tasting the flavors of the coming summer while thinking back on the 24 seasons and connecting to the history of farming?