Fukagawa Meshi—a Local Cuisine that Supported Edo

A hearty rice dish enjoyed by Edo's working class

Fukagawa is located in the western part of Koto Ward in Tokyo. It is primarily the area between Monzennakacho and Kiyosumi-shirakawa and is known for its relaxed downtown atmosphere as well as being the town where Matsuo Basho and Ino Tadataka once lived.

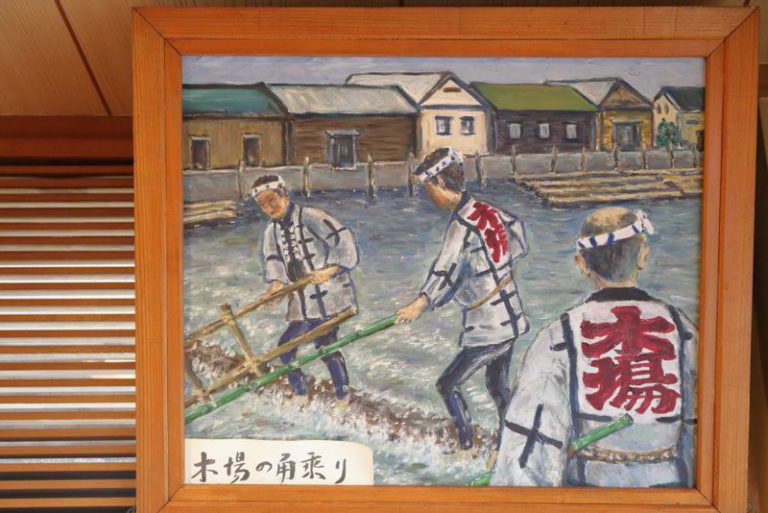

The area surrounding Fukagawa, concentrated on present-day Monzennakacho, was once a vast ocean. During the Edo period (1603–1868), Fukagawa had several purposes: it was a temple town, a timber yard with numerous lumber businesses, a warehouse area that served as a major distribution center for Edo, and a fishing town where many people toiled and contributed to Edo’s success. Fukagawa Meshi was a dish that sustained manual laborers during their physically demanding work.

Many people associate Fukagawa Meshi with a rice dish that is cooked with clams and can often be found in bento boxes sold at train stations. However, the dish originally consisted of fresh clams stewed in miso and chopped green onions, served on hot rice.

“Fukagawa was once a famous fishing town that had an abundance of shellfish, particularly clams that were known as “waku” due to their abundance. (Waku means gushing forth in Japanese.) So, clams were readily available. Back then, they served piping hot clams cooked in miso on room-temperature rice as a quick meal because they didn’t have rice cookers that could keep the rice warm,” says Maki Nittoji, the second-generation owner.

Soy sauce was still expensive back then, so people used miso to cook. Clams are rich in nutrients, and besides taurine, they contain a lot of minerals, such as iron and zinc. They are an ideal food for laborers.

When soy sauce became widely available to the public during the Meiji period (1868–1912), Fukagawa Meshi was created to make it easier for workers like carpenters to transport food in bento boxes. Until the early Showa period, Fukagawa Meshi was sold at many food stands and one-dish shops, and it was also enjoyed at home.

Nittoji commented that according to those who remember Fukagawa in those days, the town smelled of clams initially, but the scent of wood would emerge as you turned the corner.

Reviving the once-lost food culture

However, the fishing industry in Fukagawa came to an end in the 1950s due to water pollution and landfills. Opportunities to savor Fukagawa Meshi dwindled as the sea receded and fishermen vanished from Fukagawa.

However, Takami Nittoji, the founder of Fukagawajuku and Maki’s father, took it upon himself to revive Fukagawa Meshi, the town’s food culture, as a local cuisine. He was originally in the timber business but was interested in running a restaurant. He started his career when he got married.

Nittoji remembers that her parents were involved in the food industry due to her mother’s excellent cooking skills. One day, they stumbled upon a vacant lot in an area that was still populated by many timber shops. They decided to open a restaurant and bar that would serve food and sake to the many single men who worked in the area.

Nittoji mentioned that back then, there were hardly any restaurants that served Fukagawa Meshi in the area, but by the mid to late 1980s, things began to change. The Koto Ward launched a project to revive the Fukagawa area, from Monzennakacho to Morishita, as a tourist destination, preserving the Edo ambiance.

It was decided to open the Fukagawa Edo Museum in front of the Nittoji family’s restaurant and bar. Wanting to share the Fukagawa food culture from the Edo period with many people, Takami decided to open a restaurant specializing in Fukagawa Meshi.

Takami remodeled a restaurant/bar and opened Fukagawajuku in 1987. Based on the recommendation of his colleagues in the timber and carpentry business, Takami used boards from a house that was demolished and had stood since the Edo period to create the signboard, tables, and other items. This transformation turned the place into a stylish restaurant with a touch of Edo.

Fukagawa Meshi seasoned with sweet miso, using fresh clams.

Fukagawajuku offers two types of Fukagawa Meshi: the original served over rice, known as “bukkake,” and the “Hamamatsu-style,” in which the clams are cooked in the rice. During our visit, we tried the “Tatsumi Gonomi,” which allowed us to enjoy both in mini sizes. The dish is named after Tatsumi geishas, who were active in Fukagawa during the Edo period (1603–1868). The name was inspired by the idea that the geisha would probably want to eat both types of Fukagawa Meshi.

Nittoji recalls, “Before opening the restaurant, my dad asked a former fisherman to make him a bukkake-style Fukagawa Meshi. He said it was quite salty since it was traditionally eaten by the working class. He would adjust the seasoning based on the person who was going to eat it. We sought to make it suitable for all kinds of people, from small toddlers to senior citizens, and came up with a sweetened miso version.”

Bukkake is enjoyed by mixing rice with a steaming sauce. Maki’s mother, Kimiko Nittoji, a Nagano native and an expert in using miso, created a secret recipe miso blend of red and white miso, which has a comforting taste. On the other hand, the takikomi style is light and elegant. It would taste morish as onigiri rice balls.

The clams, which are essential to the dish’s flavor, come from a shellfish shop in Urayasu that the family has known for years. Nittoji insists on using freshly caught clams instead of frozen ones, resulting in clams that are odorless and delicious even without ginger.

Nitto explains, “Clams are caught extensively from Hokkaido to Kyushu. However, there is a specific texture and size that is ideal for Fukagawa Meshi. Large and meaty clams are best steamed in sake but overpower rice in Fukagawa Meshi.”

Maki presented us with some delicious-looking plump clams, saying, “Take a look at these beautiful clams I got today.” She informed us that the clams are at their sweetest during May and June when they fatten up for spawning.

Passing down Fukagawa's history and culture to future generations

Today, Fukagawa Meshi is now widely available in soba noodle shops, Chinese restaurants, and izakayas and is no longer limited to specialty restaurants.

Fukagawa Meshi has a unique flavor that will make you want to come back to Fukagawa. It is similar to home cooking, where every family has their own distinct taste.

Fukagawajuku Honten attracts a diverse range of customers, including young couples, friends exploring Kiyosumi-shirakawa, seniors citizens, and an increasing number of tourists from Asia and Europe.

Maki has deep affection for Fukagawa, where she started working with her predecessor at the restaurant when she was 21 to learn the ropes. She took over the restaurant in 2016.

Maki explains, “I have a deep affection toward Fukagawa, as it played a significant role in my upbringing. As a child, I spent most of my time playing around the temple and interacting with my elderly neighbors. After graduating from high school, I went to the United States to study English for two years. During my time there, I had to talk about my hometown in class, and it made me realize how special it is to have so many stories to share about Fukagawa. I want to spread awareness about Fukagawa Meshi to preserve its history and culture for future generations.”

The Fukagawa Meshi Promotion Association, of which Fukagawajuku is a member, showcases the dish at various events such as the Koto-ku Festival and the Tokyo Marathon. They also exhibit its history and share its appeal at shows. Maki also plans to demonstrate how to make Fukagawa Meshi at elementary and middle schools.

We felt very hopeful that the culture of Fukagawa Meshi has been revived by the efforts of people who love the town and will continue to spread further through these initiatives.