Chestnut Farmer in Kasama Questions the Future of Food

Visiting Kasama, Ibaraki Prefecture, Japan's leading chestnut growing area

Chestnut cultivation in Japan has a long history, with origins dating back to the Jomon period (c. 14,000-300 BCE). Carbonized chestnuts have been unearthed around the country, including at the Sannai-Maruyama Ruins in Aomori, Aomori Prefecture.

They also appear in the Records of Ancient Matters, The Anthology of Myriad Leaves, and Chronicles of Japan. They are said to have spread to various parts of Japan during the Edo period (1603-1867), when daimyos (feudal lords) made their obligatory trips to the capital.

Chestnuts worldwide are roughly divided into four types: American, European, Chinese and Japanese. Japanese chestnuts are larger and have more water content than others, making them moist and pleasant to eat when boiled. The ones commonly enjoyed as waguri are Japanese chestnuts.

While many production regions are dotted around Japan, including Kyoto, Kumamoto and Ehime Prefectures, Ibaraki Prefecture boasts the highest yield and shipment volume. According to the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries’ statistics, Ibaraki shipped 3,090 tons in 2019.

The total area under cultivation is approximately 1,710 hectares. Kasama, located at the center of the prefecture, accounts for 30% of the total area under cultivation. The volcanic ash soil in the area is suitable for growing chestnuts, and you will see chestnut trees here and there when you drive along the main road that runs through the city. The Iwama area is particularly famous for its chestnuts, and it has a concentration of chestnut farms and processing plants.

Besides diversifying agriculture through private-public partnerships and inviting the public for recipe suggestions, Kasama hosts the Kasama Shin-Kuri Festival every fall, where freshly picked chestnuts and chestnut products are assembled. The city is trying to raise the profile of Kasama’s chestnuts.

There are eight varieties of chestnuts grown in Kasama, including Porotan, Rihei, and Ginyose. Depending on the variety, chestnuts vary significantly in character, and their complexity is astonishing. They vary widely from Tanzawa, which yields a high amount of chestnuts with vibrantly colored meat, to Tsukuba, which have a rich flavor and moist meat, and Ishizuchi, which are suitable for stewing in their astringent skin as they hold their shape.

The length of the growing season also differs with these varieties. The season is divided into wase (early), nakate (middle), and okute (late). Chestnut farms take advantage of these periods to manage their fall shipments, sending out wase varieties in early September and okute varieties in late October.

The Hitomaru chestnut is especially rare and regarded as the “phantom chestnut.” This variety, developed in 1985, is characterized by its glossy, reddish-brown shell. It is rarely seen in the market as it is smaller and more labor-intensive to harvest. However, its soft meat is sweet and fragrant. Since Hitomaru chestnuts are suitable for processing, an increasing number of stores have used them in desserts in recent years.

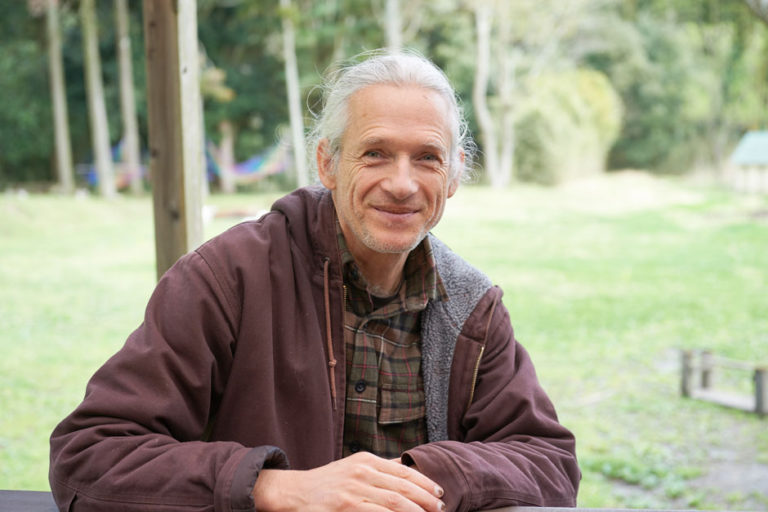

The chestnut farmer captivated by the rare Hitomaru variety

Shinya Saoshiro, a chestnut farmer, is one such person who became fascinated by Hitomaru’s allure. He grows Hitomaru on three hectares of farmland in the city. He is based in Tokyo but commutes to the farm for half the week.

He used to work for a design company in Tokyo. His turning point came in 2009 when he visited Kasama in search of ingredients for a dessert he was creating. He was impressed by the chestnut paste he tasted for the first time at Odaki Shoten, a chestnut processing specialist with a history of nearly 60 years. Since then, he has come to revere the president of the plant, Yasuhiko Odaki, as the “chestnut master.”

“I was amazed, as it tasted unlike anything I tried before. I had been involved in many food-related projects, but most of them were embellished by branding. I somehow felt uneasy about that. I wanted to preserve Japan’s wonderful food culture for future generations, not just produce it superficially. That desire has served as the starting point for me to dive into the world of chestnuts,” says Saoshiro, recalling his encounter with chestnuts.

We visited Saoshiro’s farm in the middle of the harvest season. Saoshiro silently picked up chestnuts, wiping off the sweat running down his face. He uses no pesticide or fertilizer to create the most natural environment. Naturally, he puts a lot of effort into growing the chestnuts. Last spring, there was a massive outbreak of moth larvae that ate away the leaves. Despite this, he says matter-of-factly that “pesticides and fertilizers are used for the farmer’s convenience.”

It has been about five years since Saoshiro began growing chestnuts in earnest, and they are all he thinks about night and day. Sometimes the yield is not worth the effort, as, every year he is at the mercy of the weather. When asked if there are times that he feels his deepest love turning into the deepest hatred, he smiled and said, “I’m grateful, never hateful.”

“For me, they are shiny, lovely chestnuts. I’m often told that I spend a lot of time on them, but I’m not even aware of that. They have to be safe for people to eat.”

Premium Mont Blanc made with a luxurious amount of Hitomaru

Saoshiro is also a pastry chef, and his skills are fully demonstrated at Waguriya, a specialty waguri store he runs in Taito, Tokyo.

The chestnuts he harvests are used in the store’s signature dish, Mont Blanc, as well as in parfaits, ice creams and cream puffs. He believes in serving products with an emphasis on freshness.

The main attraction at Waguriya is the HITOMARU Mont Blanc, served only in the fall. A generous amount of Hitomaru chestnut cream is piped over a base of fresh whipped cream and meringue placed in the center of the dish. As you take a bite, its rich flavor fills your mouth, and the mellow sweetness lingers. Although it tastes light, one serving of it can fill both your stomach and soul.

While leading the recent waguri Mont Blanc boom, Waguriya opened a sister store, Mont Blanc STYLE, in Shibuya in 2018. The selling point at Mont Blanc STYLE is that dishes are prepared right in front of customers. The interior décor is designed to look like a sushi restaurant “because both sushi and Mont Blanc taste the best when they are freshly made,” says Saoshiro.

As the store became so popular that it became difficult to obtain numbered tickets, even for customers who came on the first train, it introduced a membership reservation system in March 2021. Members rush to reserve their places as soon as an announcement is made, so Mont Blanc STYLE has now stopped accepting new membership applications.

“I want to pass on the culture of waguri to the future.” Saoshiro continues to question how food should be understood in society, armed with the Mont Blanc that represents his passion.