Steam clouds illustrate the passion behind sake making

Sake is generally made from rice, water and a fermentation starter known as koji, though sake makers often use different ingredients and different proportions. There are countless boutique sake makers in Japan using ingredients and techniques tailored to local conditions and availability of produce. The result is a rich variety of different sake varieties to try.

In order to find out more about sake, the Shungate team visited Toyokuni Shuzo in Furudono-machi, Fukushima Prefecture, where they have been making sake exactly the same way for the last 180 years.

Making sake in winter in line with local tradition and culture

Toyokuni Shuzo, founded 180 years ago in the town of Furudono-machi (Ishikawa-gun) in southern Fukushima Prefecture, is the home of the wildly popular Azuma Toyokuni brand, winner of the National Sake Tasting Association Gold Prize for nine years in a row.

Toyokuni Shuzo insists on producing sake the traditional way, during the cold winter months from November through March. The premium daiginjo sake, which is the most labor-intensive product in the range, is made in an intensive burst during the coldest week of winter, close to the first day of spring.

Winter is good for sake making because the cold, dry air helps to suppress unwanted bacterial activity that can interfere with the fermentation process.

Also, since winter is the off season for farming, it is much easier to find workers. This is why winter is a popular time for sake-making in the snowy regions of Japan.

Constant monitoring is essential

The sake maker’s day begins at 5:30 in the morning, when the air is still bitterly cold.

(Today, the temperature is a chilly 2-3°C.) The voices of the sake makers echo around the cold walls of the dimly lit brewery room, built 130 years ago.

The workers swap pleasantries and then start work as always, toiling away diligently among the clouds of steam. Sake-making is an exercise in teamwork: no effort is wasted and every person knows their role.

We speak to young Kensei Yanai, ninth-generation sake maker at Toyokuni Shuzo,

who currently acts as both kuramoto (brewery operator) and toji (the sake maker with ultimate responsibility for the finished product).

Sake making process at Toyokuni Shuzo

1) Washing and steeping the rice

Special sake-making rice is delivered in 10 kg bags and then washed by hand. All workers are expected to pitch in and help with the washing.

According to Yanai, this first step in the sake-making process fulfills an important role by bringing all the workers together for the first time and establishing a sense of team spirit in the punishing cold of winter. It also gives them the chance to inspect the year’s rice crop first-hand and discuss the feel of the grains and the moisture absorption characteristics.

The next step is to steep the rice in water. The steeping period is carefully controlled to the nearest second in line with temperature of the water and the characteristics of the rice. Too much or too little absorption at this stage can impact on the steaming process.

2) Steaming and cooling

The rice is then steamed, to transform the starch component into glutinous paste form. The steaming conditions are carefully tailored to suit the rice variety and how refined (polished) it is, as well as the prevailing weather conditions on the day. During the steaming process the factory is quite a sight, filled with billowing clouds of pure white steam.

The steamed rice is then spread out over linen cloth. A portion of the rice is selected for use as kakemai to create moromi, the pre-sake liquid that forms the basis of the final product. This portion is left to cool in the cold winter air until it reaches the required level of absorption and saccharification. The cooling period depends on the prevailing temperature and humidity conditions on the day.

3) Preparing the koji

Another portion of the steamed rice will be used to make the koji (fermentation starter). This portion is taken to a separate room called the koji-muro. The rice is spread out on a cloth and sprinkled with seed malt, then left to ferment for two days. The action of enzymes secreted by the koji mold breaks down the starch into glucose and other products.

The koji used for premium daiginjo sake requires particular attention: the temperature has to be monitored every two to three hours, day and night, to prevent any unexpected fluctuations or variance.

4) Preparing the fermentation starter

The fermentation starter for sake, known as the shubo or moto, is prepared beforehand by cultivating yeast or kobo to ensure that a large enough quantity is available. Yeast converts the glucose into alcohol. Shubo can be made in many different ways depending on the type of sake. One common approach is sokujo-moto, which involves adding lactobacillus then waiting for about ten to 14 days.

5) Moromi (pre-sake)

The next step is to mix koji and yeast with water in a tank. After six hours, the kakemai is added to the mix.

Japanese sake is a unique form of alcohol with no equal elsewhere in the world. The sake-making process essentially involves using koji and shubo to transform rice into both sugars and alcohol simultaneously. It can be extremely difficult to control the fermentation process. For optimum stability, the additives are mixed into the tank in three lots, then the mixture is left alone for about a month to produce the moromi.

6) Testing and analysis

Testing is carried out throughout this time. The alcohol concentration and specific gravity of the moromi is analyzed almost daily and adjustments are made as required.

7) Compression/extraction of lees/heating

It is now about six weeks into the sake-making process. The moromi is extracted mechanically, then compressed to separate the unrefined sake from the lees. The compression process yields microscopic solids in the unrefined sake. These are the sake lees. The unrefined sake is left for several days to allow the lees to settle so that they can be easily extracted, leaving a clear liquid?pure sake. For optimum quality consistency, the pure sake is heated at 65°C to arrest the enzyme action. It is then matured in a storage tank. Finally, the pure sake is diluted with water to reduce the alcohol concentration for human consumption.

8) Bottling and shipment

After two heating processes, the sake is finally ready for bottling. The new sake, having been lovingly prepared, lavished with care and attention like a living organism throughout every day of a long and arduous production process, can now be shipped to sake lovers in Japan and around the world.

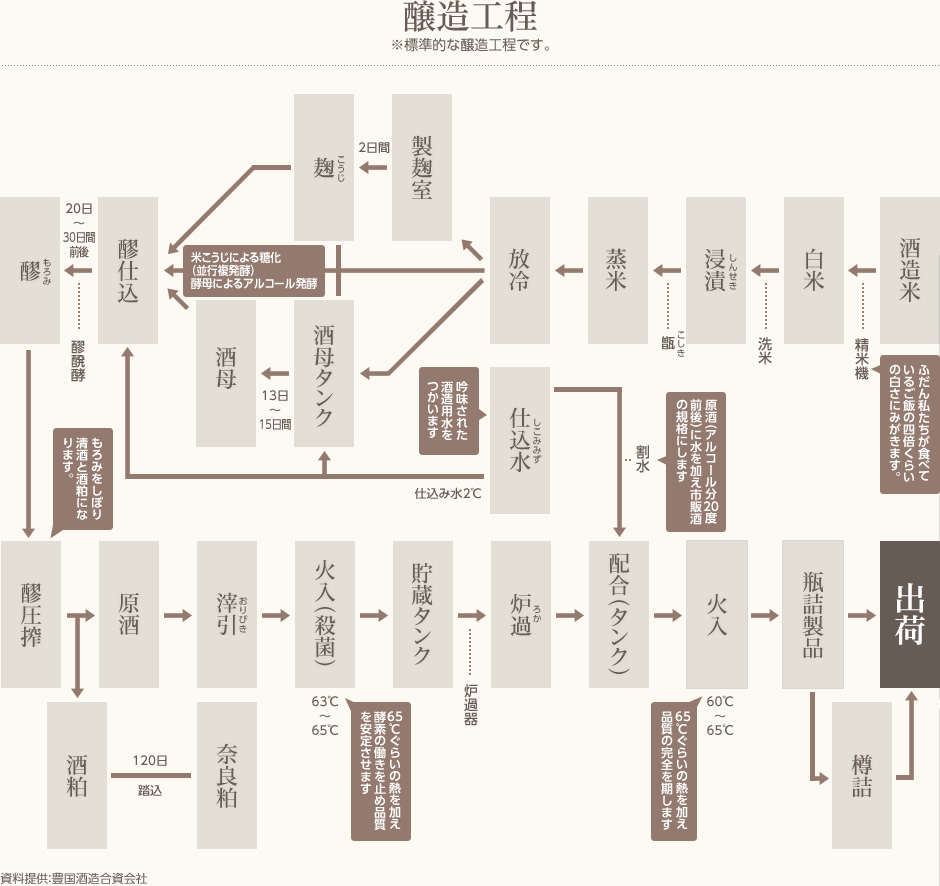

Process of brewing sake

The future of sake according to a young ninth-generation sake-maker

Toyokuni Shuzo produces more than ten different types of sake, including the legendary Azuma Toyokuni. Each one boasts its own unique combination of rice variety and production methodology. One of these, the very first sake made by Yanai when he took over the top job, goes by the name Ibuki.

Ibuki is made primarily from a rice variety called Miyama-Nishiki, which is sourced from local farms. The challenge for Yanai was to design a sake-making technique optimized to the characteristics of Miyama-Nishiki rice. The result is Ibuki.

“Furudono-machi was originally a forestry town,” notes Yanai. “The bottle we use for Ibuki is a distinctive shade of green, inspired by the forests that used to surround the old town. I’m keen to work with the local farmers on making more types of home-grown sake in the future.”

Ibuki soon came to the attention of leading chefs and sake connoisseurs, and by 2015 had become so popular that it accounted for fully one-quarter of the production output of Toyokuni Shuzo.

There are places in Tokyo to sample the acclaimed Ibuki. Cafe M/N at retail complex Marugoto Nippon, which opened in Asakusa in December 2015, stocks 720-ml bottles of Ibuki sourced direct from Toyokuni Shuzo. Why not drop in some time to try this most excellent brew, complemented by a range of carefully selected seafood and other delicacies designed to enhance the wonderful flavor.