Tracing the Origins and Spread of Sekihan, a Classic Celebratory Dish

Sekihan’s origins go back to the Asuka Period

Sekihan is served to celebrate children’s growth, long life, and other special occasions. It is a type of okowa, a widely popular recipe made by steaming glutinous rice and adzuki beans. Its red-brown color comes from the adzuki bean cooking water, which is absorbed by the glutinous rice before steaming. The cooking water is often sprinkled onto the sekihan during the steaming process. It has a sticky texture, with rustic flavors of glutinous rice and adzuki beans that become more pronounced as you chew. Its distinctive taste has gained a lot of devoted fans.

The tradition of sekihan has its roots in the Niinamesai Festival, which has been celebrated since the Asuka period. This festival is held to mark the harvest season and to give thanks for a bountiful harvest. As part of the celebrations, red rice is a votive offering to the gods. As the name “red rice” implies, it contains tannin-based red pigments, which give it the appearance of “sekihan” when cooked.

According to Kenji Kodama, SEKIHAN BUNKA KEIHATSU KYOUKAI’s secretariat member, the color red has been traditionally believed to possess the power to repel evil spirits in Japan. This is why red rice was an essential component of Shinto rituals.

The SEKIHAN BUNKA KEIHATSU KYOUKAI aims to promote Japan’s world-class food culture and increase domestic self-sufficiency through expanding sekihan consumption.

According to Kenji, there are references to adzuki porridge in the “Pillow Book” written during the Heian period (794-1185). However, it was not commonly eaten until the Muromachi period (1333-1573), when it became a dish for celebrations, but it was still mainly consumed by the privileged classes.

In the Edo period, sekihan became more similar to the dish we know today. With the development of rice cultivation technology, white rice, which had been a luxury item, replaced red rice and became popular among the populace. Still, the culture of preparing red rice for celebrations did not die out, and white rice, colored with red beans, became a popular substitute.

Eventually, sekihan became more mainstream than red rice and began to appear at various events and celebrations. In addition, nandina (nanten in Japanese) leaves are sometimes used to garnish sekihan, as a play on the phrase “nan wo tenjiru,” meaning “a blessing in disguise.” It also stems from the wisdom of the ancients, who used the preservative properties of nandina leaves in their daily lives.

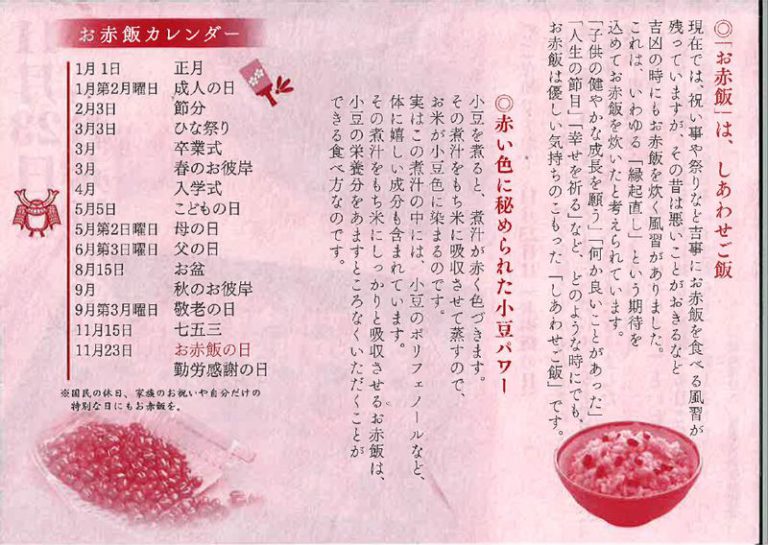

In today’s diverse lifestyles, the tradition of preparing sekihan in a formal manner has become less common. However, the Osekihan Calendar created by SEKIHAN BUNKA KEIHATSU KYOUKAI is full of events where sekihan is enjoyed. Beginning with New Year’s Day, the occasion comes around almost monthly: Setsubun no Yakunoke, Double Third Festival, Mother’s Day, Obon, Respect-for-the-Aged Day, and New Year’s Eve. When life events such as coming-of-age ceremonies, weddings, and 60th birthday celebrations are added to the mix, the occasions for sekihan become even more frequent.

Kodama shares, “It used to be quite common for people to prepare sekihan at home until about a decade ago. As a child, I would feel elated whenever I returned from school and found sekihan ready, thinking that something good must have happened that day. Rice cookers now have more functions, making it easy to make sekihan at home.”

Sekihan’s diversity is deeply connected to local ingredients

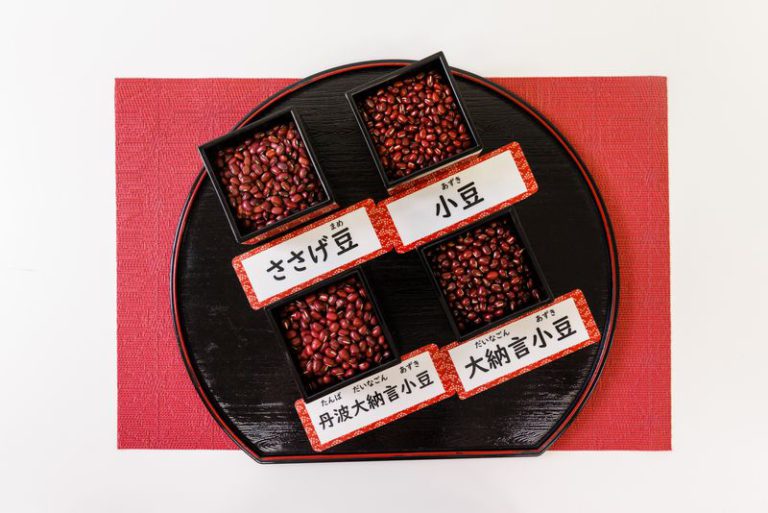

The ingredients for sekihan are not always glutinous rice and adzuki beans. Just as the ingredients and recipes for ozoni vary from region to region, so does the variety of sekihan. For example, in the Kanto region, sekihan is often made with black-eyed peas instead of adzuki beans. Despite the similar appearance of both, why are black-eyed peas favored?

According to Kodama, the superstition of the samurai warriors of Edo is linked to the use of black-eyed peas. This is because when adzuki beans are heated, the beans break in the middle, which reminded the samurai of seppuku, a ritual suicide. To avoid any association with such an act, the samurai warriors started to use black-eyed peas instead of adzuki beans.

In addition to these cases, SEKIHAN BUNKA KEIHATSU KYOUKAI also conducts research on local sekihan across the nation. Kodama introduced some of them to us.

●Amanatto sekihan

・Eaten in Hokkaido, Tohoku region, and Yamanashi Prefecture.

・It is a sweet sekihan made with candied adzuki instead of plain.

・Food coloring is used to add redness to the rice.

・It is sometimes served with red pickled ginger.

●Rakkasei sekihan

・Eaten in some parts of Chiba Prefecture.

・It is made with peanuts, a local specialty of Chiba Prefecture.

・It is made in various ways, including using peanuts cooked in syrup and cooked with adzuki.

●Shoyu sekihan

・Eaten primarily in Nagaoka, Niigata Prefecture.

・The rice is seasoned and colored with soy sauce.

・Red kidney beans are used instead of adzuki.

●Imo sekihan

・Eaten primarily in Ono, Fukui Prefecture.

・It is made with adzuki and taro, a local specialty.

●Sanshoku sekihan

・Eaten primarily in Yanagawa, Fukuoka Prefecture.

・Rice colored with dried gardenia pods and adzuki is mixed with mochi rice.

・The sekihan produced is colorful with shades of red, yellow, and white.

●Gomazato Sekihan

・Eaten primarily in the Naruto region of Tokushima Prefecture.

・It is a sweet sekihan sprinkled with toasted sesame seeds and sugar.

Kodama notes, “Further investigation is needed to understand the origins of regional sekihan. It may be that the dishes were created by adapting local specialties in different regions, as seen in examples like rakkasei and imo sekihan.”

SEKIHAN BUNKA KEIHATSU KYOUKAI designated November 23 as Sekihan Day in 2010 to preserve its history and tradition, which has been an essential part of Japanese people’s celebratory meals and dining tables on special occasions since ancient times. November 23 is a day to give thanks, as it is also the day of the Niinamesai Festival and Labor Thanksgiving Day. Every year, the association offers free sekihan at Forest Terrace Meiji Jingu, located on the approach to Meiji Jingu Shrine in Tokyo. Kodama hopes that the event will encourage people to take a fresh look at the culture of eating sekihan. It goes without saying that sekihan, enjoyed since ancient times, is delicious. When a special occasion is combined with it, the feeling of satisfaction after eating it is even greater.