Toshikoshi Soba, A New Year’s Eve Feast Enjoyed by All

In this issue, we asked Yoko Okubo, a scholar of early modern food culture with in-depth knowledge of Edo period (1603 - 1867) food culture, to unravel the historical background of toshikoshi soba. We also visited the famous restaurant Kanda Matsuya, which sells as many as 8,000 servings in a day on New Year's Eve, to report on the modern-day toshikoshi soba scene. You might be able to enjoy toshikoshi soba with a different mindset this year.

Soba noodles became a regular menu item at the end of the month. Edo's soul food was a part of daily life

It is said that soba noodles, in our familiar noodle form, were introduced into the lives of the masses in the 1700s. The area around present-day Ginza in Tokyo was a thriving merchant town, and soba became a popular fast food to fill the stomachs of workers who earned their daily wages. One can imagine how they flourished since it is said that there were as many as 3,700 soba restaurants in Edo, a city smaller than the 23 wards of Tokyo today, at the end of the Edo period.

According to Okubo, since the word toshikoshi soba appears in a document called Osaka Hanka Fudoki (1814), it is thought that toshikoshi soba was eaten in Osaka during that period.

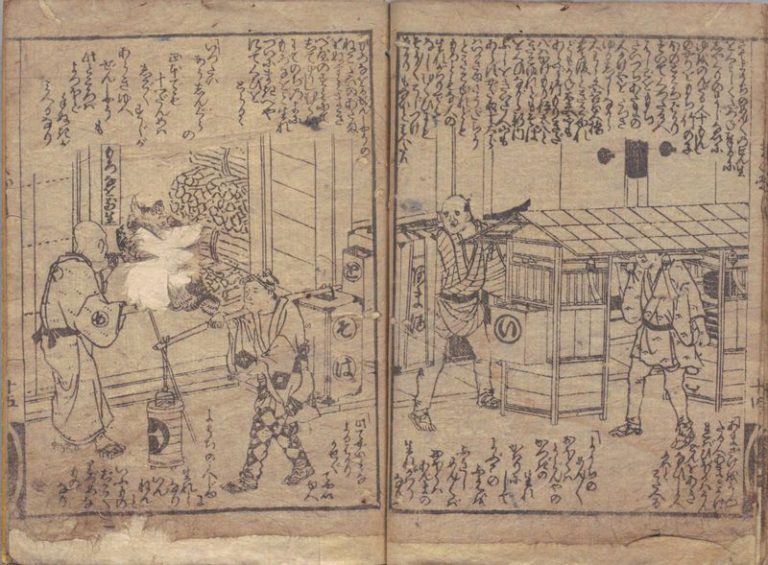

Soba has long been eaten as food made of flour (soba mochi, soba gaki, etc.), but its noodle form supposedly originated in temples from the Muromachi (1336 – 1573) to the Edo period. It was especially during the Edo period that it became popular among ordinary people, and by 1772, food stalls selling sushi, soba noodles, and other dishes were in vogue throughout the city of Edo.

Okubo explains, “I believe one of the reasons why soba noodles became more popular than udon in Edo is that they take less time to cook than udon.”

Okubo speculates that a more common custom of the townspeople may have evolved into toshikoshi soba.

Okubo expounds, “In the Edo period, merchant families and farm households with tenant farmers would decide on their menu; for example, the fifth day of each month was fish day. Eventually, the custom of eating soba noodles on the last day of the month in urban areas like Edo became prevalent, known as misoka soba. The word misoka means the last day of the month, and eating soba noodles on the last day of the month was also a way to celebrate getting through the month without a hitch. I think deciding what to eat and on what day was rational in preparing daily meals. In Edo, it appears that people ordered and ate heaping soba noodles on the day of susubarai, a year-end event to clean the house inside and out. Thus, misoka soba gradually became limited to New Year’s Eve. The name toshikoshi soba did not take root until much later. In other words, the custom of Edo, where restaurants were well established, eventually spread to the countryside.”

Pondering on the hopes of the people enjoying toshikoshi soba

Soba noodles bring good luck in longevity because they are long and thin, the easily broken noodles cut ties from the passing year’s ill luck, and soba attracts money since gold leaf craftsmen use sticky soba gaki to collect tiny specs of gold dust. All of these benefits are worth taking advantage of at the start of the New Year.

According to Okubo, the very fact that toshikoshi soba has been eaten to express the wishes of people from all walks of life holds real significance.

Okubo further explains, “We accept eating toshikoshi soba at the end of the year as a given, but I want people to take an interest in its origins. The end of the year was a tough time financially for the denizens of Edo, as evidenced by the commoners settling their accounts with the merchants. In this lifestyle, the custom of eating soba noodles developed, with people playing on words or creating bywords for luck. Some of them would have been glad to be able to eat soba noodles as everyone else, at least on New Year’s Eve, after toiling day after day to make ends meet. Soba also contains vitamins B1 and B2, which helped prevent beriberi among people in Edo who ate only white rice and suffered from the condition, and it was also an affordable, tasty and healthy fast food.”

Incidentally, Japan has various styles of soba cuisine according to region. Typical examples include hegi soba in Niigata Prefecture, which uses funori (red algae) as a binder, nishin (Pacific herring) soba in Kyoto and Hokkaido, and grated daikon (mooli) in Fukui Prefecture, but do these cultures also influence toshikoshi soba?

“There doesn’t seem to be a rule that the local soba dish is the toshikoshi soba. No document says which soba noodles are decided as toshikoshi soba, which may vary from household to household. It would be fun to choose a local version, like ‘This year, let’s do it Niigata style!’” says Okubo. Toshikoshi soba can be enjoyed as you please. It seems okay to welcome the New Year with your favorite soba.

The custom of eating toshikoshi soba has taken root among a relatively wide range of age groups, as even young people eat cup-noodle soba on New Year’s Eve.

“We don’t know what will happen in the future, but it’s nice to have a custom we can all share and make wishes this way,” says Okubo.

Kanda Matsuya, an Edo-style soba noodle restaurant, has the longest queue in Japan on New Year's Eve

Kanda Matsuya, established in 1884 in Kanda, Tokyo, is said to serve the best toshikoshi soba in Japan because every year, there is a massive line of people waiting to eat this restaurant’s soba to ring in the New Year. According to Takayuki Kodaka, the sixth successor owner who runs the restaurant, as many as 8,000 servings of soba noodles are served alone on New Year’s Eve.

“We serve a special winter solstice soba called Yuzukiri around December 20, and we’re busiest from that time to New Year’s Eve. I don’t know why customers come to us, but many of them have already decided to come to Matsuya for the toshikoshi soba. I am really grateful for that,” says Kodaka.

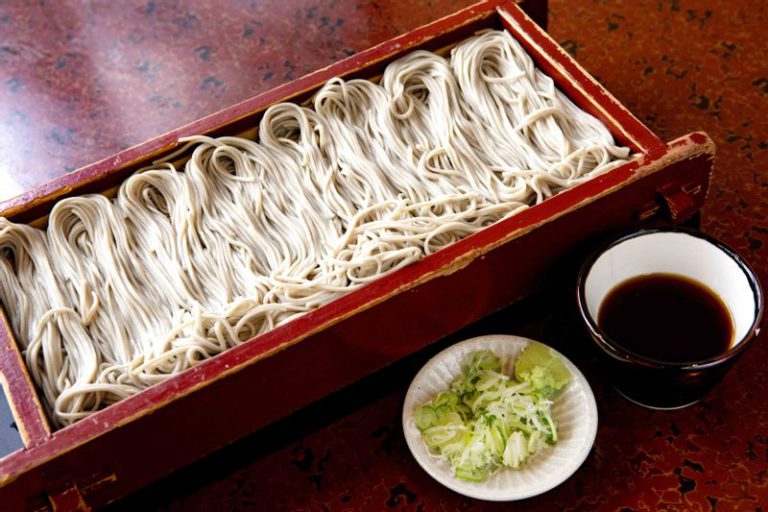

All soba noodles at Kanda Matsuya are handmade. Kodaka, a 35-year master chef, says that the most important part of making soba is to knead the buckwheat dough thoroughly in a wooden bowl and roll it out to an even thickness. Matsuya’s strong sauce, which Kodaka calls shiru, is made with dark soy sauce and dried bonito flakes, as is typical of the Edo-style soba. He has preserved the traditional taste of soba, carefully considering the balance between the soba and the dipping sauce. The buckwheat flour changes with the seasons, but Kodaka proudly claims that Hitachi akisoba buckwheat, produced in Ibaraki Prefecture, is his restaurant’s signature flavor. Its punchy and intense flavor pairs perfectly with Matsuya’s dipping sauce. The restaurant switches to Hitachi akisoba as early as the latter half of November, so you should be able to taste the best soba in time for New Year’s Eve.

“My approach to making the shiru is to make it salty to drink but tasty to eat. It tastes good when eaten with soba noodles and even better if you add sobayu (soba cooking liquid). That’s my style of shiru. I want my customers to taste both warm and chilled soba with sobayu at the end. I believe you can only preserve the taste for a generation, and although I can’t make it exactly the same as my predecessor’s, I can bring it close. I want to respect Matsuya’s taste,” says Kodaka. Behind the calm demeanor on his face, we sensed the pride he takes in Matsuya’s flavors.

Hopes for the continuation of the soba culture into the future

When does Kodaka eat toshikoshi soba?

“We eat on the morning of January 1. When we are done with the New Year’s Eve business, the whole family goes home at 4 or 5 in the morning of the 1st. Then we all nap and have soba noodles when we get up. We eat soba instead of zoni. It’s too much trouble to cook warm soba at home, so we eat cold soba,” he says. Soba eaten at the start of the New Year sounds refreshing and tasty.

Kodaka says he used to actively welcome students on school excursions before COVID-19. He has been sharing the beauty of soba with the younger generation by making soba gaki (buckwheat dumplings) with them and treating them to their favorite soba. Kodaka hopes that Kanda Matsuya and the soba culture will carry on in the future.

He comments, “Many young people come to our restaurant to eat toshikoshi soba. I’m very flattered by that. I hope they will continue to enjoy toshikoshi soba as well as soba for years to come.”