Oden, the Ever-Evolving Hotpot

The surprising origins of oden, a tradition for cold seasons

Oden is a dish that people crave when the weather turns cold. A bowl of hot oden warms the body and soul to the core. It can be made with readily available ingredients, and it is simple to prepare. It is also available in a wide variety of boil-in-the-bag products, making it a popular dish throughout the year.

Dengaku-dofu, believed to be the progenitor of oden, is a dish in which skewered tofu is coated with miso and served. How did dengaku-dofu, which looks nothing like oden, evolve into a hotpot? Nobuaki Obiki, an instructor of Japanese cuisine at Tsuji Culinary Institute, explains.

“Dengaku-dofu is believed to have become popular during the Muromachi period. Among the wives serving the imperial court, it was called o-dengaku with ‘o’ added to the first letter, which then became oden. When we think of oden, we associate it with the stewed dish, but the word referred to dengaku for a long time.”

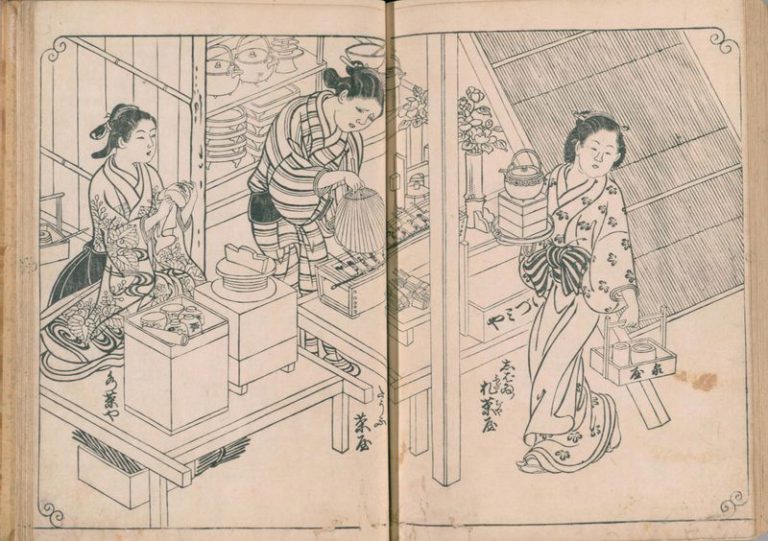

In the Edo period, more variations of dengaku became available, using ingredients such as konjac, eggplant, and fish. According to Nobuaki, oden developed the style we know today in the late Edo period. Boiled dengaku, in which skewered ingredients are stewed in hot water, appeared as a derivative of dengaku. At first, skewered ingredients were dipped in soy sauce or miso paste, but a method of stewing in soy sauce-flavored broth was subsequently established.

Nobuaki expounds, “Dengaku at that time was a kind of fast food served in food stalls and teahouses. It may have evolved from being grilled to stewed as restaurants prioritized efficiency. Eventually, stewed dengaku came to be called oden, and dengaku remains a separate item.”

Oden, formerly known as nikomi (stewed) dengaku, gained popularity among the denizens of Edo (the old name for Tokyo) and spread to various parts of Japan during the Meiji and Taisho periods. When it reached the Kansai region, it developed as Kanto-daki. This was because miso dengaku was deeply rooted as oden in the Kansai region. For Nobuaki, a native of Wakayama Prefecture, Kanto-daki is more familiar to him than oden.

“Where I’m from, it was called Kanto-daki. My mother used to make it for me. Nowadays, I think it’s more common to call it oden in the Kansai region, too,” comments Nobuaki.

Occasions for enjoying oden have changed with the times. Many people associate oden with family gatherings at the dinner table. However, Nobuaki says, “That image grew in the Showa period (1926–1989).”

“In the Edo period, people ate their meals on individual serving tables. The introduction of the chabudai (low dining table) in the Meiji period and its widespread use from the Taisho to the Showa period changed the picture. Families had more opportunities to eat together around a table. In this process, it is thought that hotpots such as oden and other dishes served on platters started to appear on the dining table,” says Nobuaki.

Diversity of regional oden featuring local flavors

As oden reached various regions, it underwent its unique evolution. For instance, a comparison of the Kanto and Kansai regions reveals that the differences in dashi cultures are reflected in the styles of oden.

Oden in Tokyo is generally based on bonito dashi seasoned with dark soy sauce. In Kansai, on the other hand, kelp dashi is the key to its flavor. The light soy sauce used as a seasoning makes the broth clear and allows the flavors of the ingredients to shine through.

The most popular oden ingredients in Tokyo are fish pastes such as hanpen and tsumire, but in Kansai, beef tendon, octopus, and hirousu (ganmodoki) are preferred.

Oden in the Chubu area, far from the cultural sphere of the Kanto and Kansai regions, is more eclectic. For example, Shizuoka-style oden is so black that you can hardly see the bottom of the pot. It is also unique in how it is eaten, with fish powder sprinkled over black hanpen (fish cake) and pork. In Aichi Prefecture, which has a well-developed miso culture, oden is served with miso paste or in a miso stew style.

Other variations include the Hokkaido style with milt and the Okinawan style with pig’s feet. Each region has its unique seasoning and ingredients. Finding the authentic one is more complex. Nobuaki couldn’t help but remark, “This diversity is what makes oden so interesting.”

Nobuaki comments, “There are Kanto and Kansai styles of sukiyaki as well, but they are similar in their finished form. However, oden has a strong regional identity and is free and original. It reflects the local food culture of the region and thus has depth as a regional dish. Then again, there are new types of oden, such as tomato oden. Oden continues to evolve because there’s no single correct oden style.”

Oden is a versatile dish, but it can be made even tastier with a little ingenuity. What is important is the dashi, ingredients, and heat level.

“First, decide on the dashi you want to use. The overall flavor will come together if you choose ingredients that complement the dashi flavor. Fish paste is recommended because it contains umami, which releases in the dashi. Root vegetables absorb the dashi and become tasty. The key is to simmer the ingredients over a low heat so the fish pastes do not lose their resiliency, and the tofu does not stiffen. Once you get the hang of it, try exploring your own oden style, such as Thai or Chinese,” says Nobuaki.

The pride of a long-established oden store, using adversity as a springboard for revival

There is an oden restaurant that has preserved its traditional taste for almost a century. Founded in 1923 in Ginza, Nihonbashi Otakou Honten moved to its present location in the commercial district of Nihonbashi, Tokyo, in 2002.

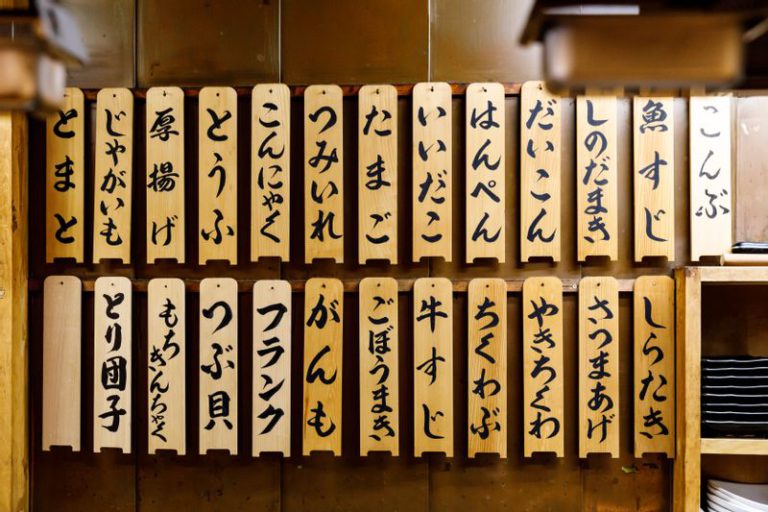

Once seated at the counter facing the kitchen, the oden pot is right in front of you. Just looking at the steam rising from the pot will whet your appetite. The restaurant serves over 20 kinds of oden items. The selection is dazzling, from daikon to egg, grilled chikuwa (fish paste), tofu, and hanpen.

“We get our hanpen from Kanmo, a well-established kamaboko (fish paste) store in Nihonbashi,” says Junya Yoda, the restaurant manager. He starts preparing ingredients in the morning to be ready to open at night when customers arrive constantly. Daikon is the most popular among the variety of oden items, but shinodamaki, a fish paste wrapped in fried bean curd, also has many fans.

The brown broth is Kanto style, with an addictive sweet and savory flavor. Junya’s taste cannot be replicated if the sauce is too sweet or too salty. The chef monitors the pot daily and strives to strike the perfect balance.

“We have been using the broth for decades, adding to it as we go along. The flavor base is bonito and kelp dashi, soy sauce, and sugar. The umami of the various oden items dissolves into it, creating our flavor. I rely solely on my palate when checking the taste, so I am always vigilant,” says Junya.

Otakou Honten, a prominent name in Nihonbashi, was also forced to close its doors due to the COVID-19 pandemic. After patiently enduring the crisis, it reopened for business in February 2022. Junya is eager to revive the restaurant.

“We’ll also revive our famous rolled cabbage, which we had stopped serving for a while. We want to incorporate a new style into the restaurant while making the most of the good old ways,” says Junya.

With its roots in dengaku-dofu, oden evolved into a one-pot dish distinct from the original. It has shown generosity in accepting local food culture in its entirety and has branched out in various directions. It is still unknown how much regional oden will expand and what possibilities long-established restaurants have. Even in the Reiwa period (2019–), the evolution of oden continues unabated.