Yokan—A Sweet that Evolved while Being Nurtured by Japan’s Culture and Climate

Toraya Confectionery, a traditional Japanese confectionery company founded in Kyoto in the early 16th century, is one of the famous yokan makers in Japan. For this article, we spoke with Tamaki Morita, senior archivist at Toraya Bunko (Toraya Archives), which is an establishment that houses documents related to Japanese confections and has also published an authoritative book on yokan. We asked her about the profound world of yokan, its roots in China, as well as how it developed to become a Japanese confectionery, along with the colorful variety of regional yokan.

Originally a Chinese mutton stew, yokan underwent a unique evolutionary process to become a confectionery.

“Yokan was originally a dish enjoyed in China before the first century. The word yokan is composed of two characters which gives it its literal meaning: the first character ‘羊’ referring to sheep, and latter ‘羹’ meaning stew. We think it was a very luxurious and scrumptious dish. ” says Morita.

Yokan was first introduced to Japan during the Kamakura and Muromachi periods (spanning from the end of the 12th century to the latter half of the 16th century). Zen priests who studied in China brought this dish back with them along with the Chinese custom of tenjin. At the time, people only had two meals a day—once in the morning and once in the evening—and tenjin was a light snack to eat between meals. Yokan was one of many tenjin dishes.

“It is believed that yokan still resembled the original Chinese dish when it was introduced to Japan. However, as it was forbidden for Zen priests to eat any meat, we believe they substituted sheep meat with plant-based ingredients such as azuki beans or flour. Unfortunately, there are no recipes of these dishes left now, but it is said that the substitute for this meat is the origin of what became mushi yokan (steamed yokan).”

Although yokan was first eaten in temples, it gradually became popular among aristocrats and warrior families alike. Yokan was considered an exotic delicacy from overseas and was often served as one of the dishes when entertaining guests among warrior families: a custom based on aristocrat banquets of that era.

There are illustrations of yokan in the ‘Shokumotsufukuyo-no-maki’ (Documents on Food Etiquettes; circa 1504), a late-Muromachi period (1333–1573) record on food etiquette for warrior families. The yokan depicted here is served on a formal tray with condiments and pickled plum, while the soup is prepared separately.

“During the Warring States period, there were frequent rituals in which the lords visited their subjects’ residences and accepted their hospitality. These rituals were called onari, and yokan was featured on such banquet menus. Records say that yokan was initially offered as an appetizer to accompany sake, but it was also offered as a type of sweet as time went on.”

Evolution of yokan as a confectionery

During the Edo period (1603-1867), it became uncommon to eat yokan as part of a meal, and this dish started to be known as a confectionery. There is an entry on “yokan” and “sugar yokan” in the Portuguese ‘Vocabvlario da Lingoa de Iapam’ (Japanese-Portuguese dictionary)(1603) which states that yokan was made by kneading beans together with unrefined sugar, whereas sugar yokan was a slab-shaped confectionery created from beans and presumably white sugar. The “beans” in these entries are thought to refer to azuki beans.

“It is believed that the method of shaping yokan by kneading dough made from azuki beans and flour gradually became simplified, resulting in the current bar-like shape of mushi yokan becoming mainstream.”

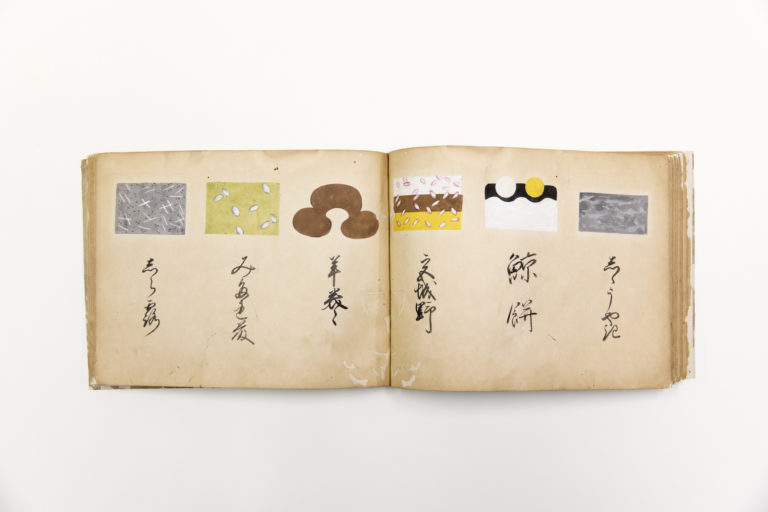

Illustrations from the Edo period also show yokan without its usual square shape. Looking at Toraya’s 1695 illustrated book of confectionery designs (the equivalent of a catalog in the present day), we can see yokan with a suhama shape (a design with an intricate coastline motif).

“We believe that the yokan seen here was created using a traditional method that involved forming them into shapes. As a matter of fact, some present-day fresh confections by Toraya are derivatives of such techniques. This method is called ‘yokansei’ (more widely known as “konashi”), in which azuki bean paste containing flour and glutinous rice powder is steamed, kneaded and molded into various shapes.”

There are also written records in the 1700s on mizu yokan (soft gelled yokan). It seems that mizu yokan was initially created by simply increasing the water content of the original recipe, but mizu yokan solidified with kanten (agar-agar) also appeared around this time.

“Toraya has a technique called ‘mizu-yokansei’ in which azuki bean paste is mixed with sugar and kuzu (arrowroot) starch, and then the steamed dough is molded. We believe that this technique derives from the traditional method of making mizu yokan.”

It is said that neri yokan (gelled yokan), the mainstream variety of yokan today, was originally created in the latter half of the 18th century. This type of yokan adds agar-agar to azuki bean paste, and the mixture is thoroughly kneaded together for a smooth but firm texture and a long shelf life. Neri yokan turned out to be immensely popular in Edo (current day Tokyo) and it spread out throughout the country within a few decades.

“Neri yokan became widely consumed in Edo. However, the main product of Toraya—a company that had been doing business in Kyoto during this period—was still largely mushi yokan. The term “neri yokan” did not appear in any Toraya records until the end of the Edo period.”

A diverse array of yokan from each region and season

In the modern day, there are many ingredients, shapes, and manufacturing methods for what we call “yokan.”

“Although a concrete definition is difficult because of the wide variety of ingredients and manufacturing methods, in general, we can use the term yokan to refer to a confection which is a solid mix of azuki beans and sugar.”

Regional yokan showcasing various ingredients exist across Japan, and it is believed that the industrial development during the Meiji period (1868–1912) played a significant part in this.

The development of railroads and other transportation networks resulted in a surge of tourists, and the demand for souvenirs soared. National industrial exhibitions were held and the government promoted the creation of specialty goods using local products, resulting in the birth of many local yokan.

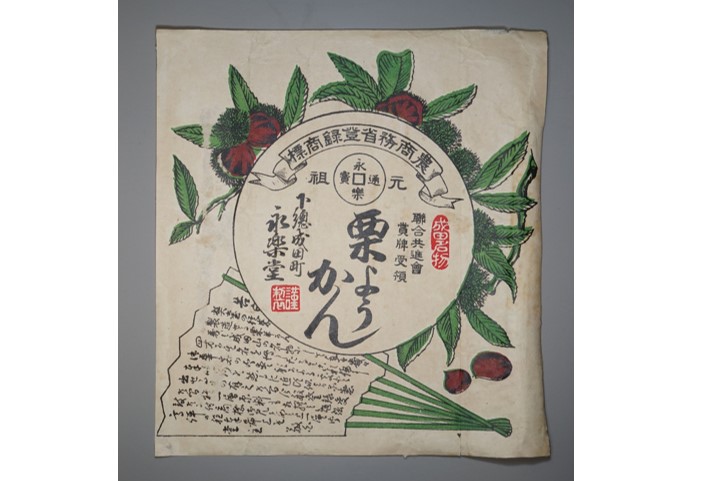

“Different types of local specialty yokan were created at tourist spots featuring sights of interest such as shrines, temples, and other historical sites. The confectionery’s long shelf life and ease of carrying around made it immensely popular among travelers. Old merchandise labels from the Meiji (1868–1912) to Showa (1926–1989) periods display yokan named after locations such as ‘Famous Nara Great Buddha Chestnut Yokan’ or ‘Famous Narita Chestnut Yokan’ (Chiba Prefecture), and there were also yokan using famous local produce such as persimmon, strawberries, Japanese parsley, and wasabi.”

There are also seasonal yokan. Toraya sells yokan featuring seasonal motifs such as cherry blossoms in March and wisteria in April, allowing customers to enjoy the changing seasons.

“There are about 470 bar-shaped confectioneries, including yokan, in Toraya’s 1918 illustrated book of confectionery designs. Although this document is over 100 years old, it is still used as reference when creating and selling sweets.”

Moreover, although mizu yokan is usually enjoyed during the summer, some regions such as Fukui Prefecture have a custom of eating it in the wintertime.

The cold winter weather solidifies the mizu yokan, making it optimal for long-term storage.

New types of yokan that appeal to the modern consumer are also coming out in rapid succession.

“There are yokan featuring ingredients such as chocolate, dried fruits and nuts, yokan featuring designs like piano keys, yokan that display a different design when sliced, and many more. There are so many different types of yokan being made around Japan.”

Evolving from a Chinese sheep meat stew to a confectionery, yokan has been introduced to Japan and developed within the country’s climate and culture, taking on various forms and handed down through the generations. From traditional to innovative yokan, we can look forward a diverse array of yokan in the future as well.

References: Toraya Bunko, ‘Yokan’, SHINCHOSHA, 2019 (Japanese) / Booklet for the Toraya Bunko YOKAN exhibition, Toraya, 2019