Tracing the History of the Fermented Beverage, Amazake — From an Offering to the Gods to a Favorite of the Common People

Two types of amazake, each with its unique character, are distinguished by their production methods.

Amazake, a traditional Japanese sweet beverage, has a history of more than 1,000 years. In ancient times it was used as a noble offering, and even today, it is enjoyed as a ceremonial drink on New Year’s Eve, Momo-no-Sekku (Peach Festival) and other occasions.

Let us review the different types of amazake before unraveling its long history. Amazake is mainly divided into two types: koji amazake and sake kasu amazake. The manufacturing process varies widely in each, and these differences are reflected in the taste and flavor.

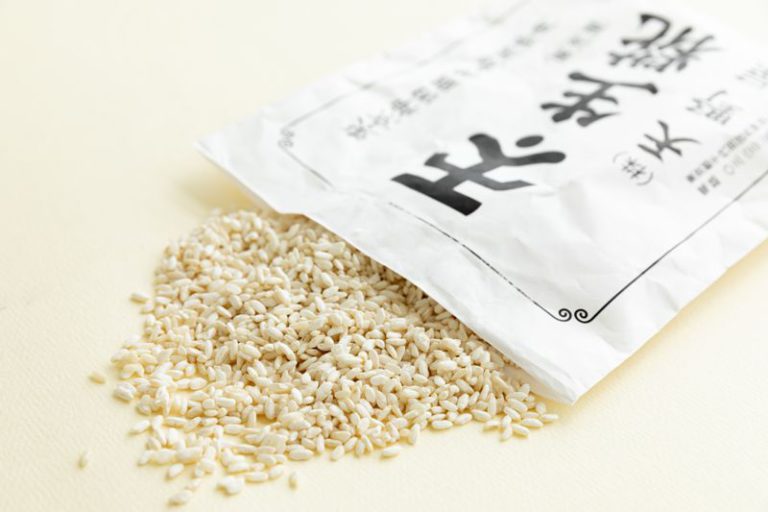

In koji amazake, the rice malt holds the key to its flavor. With a simple production method, steamed rice, rice malt, and water are stirred and fermented to complete the process overnight. During the fermentation process, enzymes in the rice malt hydrolyze the rice starch into glucose, maltose, and other sugars. This “saccharification” process brings out the natural sweetness without using sugar. Since it does not contain alcohol, it is classified as a soft drink when it goes to market. Even people who cannot tolerate alcohol and children can enjoy it.

Sake kasu amazake, on the other hand, uses sake lees as its main ingredient. Sake kasu is the solid mass that forms when sake mash is pressed during the sake production process. Dissolve this in hot water, sweeten it with sugar, and it is ready to drink. While koji amazake has a milder taste, sake kasu amazake has a unique rich flavor. However, even though sake lees have been heated, they still contain trace amounts of alcohol.

Let us also focus on amazake’s functional properties. Recent advancements in the research of amazake’s components confirmed that it contains amino acids, vitamins and other nutrients. Oligosaccharides and glucose in koji amazake provide an energy source for the body. The protein called resistant protein contained in sake kasu amazake can reduce cholesterol intake and help people lose weight.

Nutritional drink of the Edo people, approved by the shogunate for its effectiveness

Amazake’s existence is mentioned in history books beginning with the “Nihon Shoki (Chronicles of Japan)” compiled in the Nara period (710–794). According to the chronicles, around the year 288, an indigenous people of ancient times offered kosake to Emperor Ojin. Kosake is a liquor made from rice and koji (malted rice), and the roots of koji amazake can be traced to this type of liquor.

Ama-no-tamu-zake, also described in the “Chronicles of Japan,” is also considered a prototype of amazake. This sake was brewed to celebrate the birth of a child by the goddess Konohana Sakuyahime, mentioned in Japanese mythology.

In addition, kasuyu-zake, sake lees dissolved in hot water, is mentioned in a poem by the Nara-period poet Yamanoue no Okura, entitled Hinkyu Mondoka. It is a poignant portrayal of the desolation of the simple folk who warm themselves on cold nights by drinking kasuyu-zake.

Source:NationalDietLibraryDigitalCollections

In the Muromachi period (1336–1573), amazake peddlers emerged, and during the Edo period, koji amazake became widespread among the general public. Its production method seemed to have already been established, and many samurai made amazake as their side jobs.

Today, amazake is often thought of as a winter drink, but it was consumed year-round by the masses in Edo (present-day Tokyo). It was a necessity, especially in summer, and was valued as a nutritional supplement to prevent summer fatigue and relieve exhaustion. The shogunate set a maximum price for amazake in recognizing its benefits. Affordability also helped promote its widespread use.

However, circumstances changed drastically after the end of the Taisho era (1912–1926). The Great Kanto Earthquake and the Great Tokyo Air Raids followed, forcing many amazake vendors out of business. Soon after, Japan was thrust into a period of rapid economic growth, and the lifestyles of everyday people began to change. Amazake became more of a ritual drink as it faded away from people’s lives.

However, the long period of inactivity ended in the 2000s. Amazake’s health and beauty benefits attracted renewed attention, leading to a boom in the market. The fermented food craze also provided a tailwind for sake brewers and brewing companies to enter the market. In addition to drinking, amazake has also been used in cooking and desserts and continues to evolve.

The taste of a famous shop with a five-day preparation process has been loved for over 170 years

Located in Tokyo’s Chiyoda-ku, the shop is a few minutes’ walk from JR Ochanomizu Station on Nakasendo (Route 17) in Akihabara’s direction. A teahouse retaining its old-fashioned look appears beside the torii gate of Kanda Myojin Shrine, Edo’s main Shinto shrine. Amanoya is an amazake store boasting a history of over 170 years. They have been making koji amazake using the same production method that has remained unchanged since the Edo period.

Soon after arriving, we had a chilled glass of amazake. The milky, mildly sweet liquid was easy on the palate and gradually replenished the body weary from walking under the scorching sun.

“Isn’t it easy to drink? We don’t add any sugar or aroma,” says the proprietress.

We spoke with the proprietress’s, Fumiko Amano. Fumiko and her sister married into the Amano family about 60 years ago, and she runs the shop with her sister Sumiko.

“We’ve been able to do well for decades thanks to the amazake we drink daily. We’ve seen more young couples and foreigners visiting our store over the past few years, perhaps because the benefits of amazake are being recognized again,” says Fumiko.

Amanoya’s amazake is made in an underground chamber called a muro, dug six meters underground. The loamy layer of the Kanto plain, stretching across the area, is firm, making it ideal for building chambers. The room temperature is also kept constant, making it a perfect environment for cultivating koji, which dislikes sudden temperature changes. Because of this, the Yushima Plateau in the Edo period had nearly 100 amazake shops lining its streets.

The seventh-generation owner, Daisuke Amano, preserves the taste of this long-established business that has prevailed in the battleground of amazake. He has been in the business for 18 years, grew up on amazake as weaning food, and as a child, the muro served as his playground.

“Making amazake is a man’s job. This is Amanoya’s tradition. We don’t have a recipe or manual, so we learn it by doing,” says Daisuke.

Amanoya’s amazake is made in five days, including the preparation of the koji. On the first day, uruchi mai (non-glutinous rice) is washed and soaked in water, and on the morning of the second day, that rice is steamed and placed in an agitator.

Then, multiple koji molds are sprayed, and the mixture is sent to the underground tokoba. The rice, made sticky by the koji molds, is wrapped in a blanket and allowed to rest for a while.

In the evening, the blanket is unwrapped, and the tokomomi process begins. The temperature and moisture content are checked while loosening the clumped rice by hand. The next day, the temperature is adjusted so that the rice is at about 42 degrees Celsius.

On the morning of the third day, the rice is transferred to the fermenter to facilitate fermentation. On the morning of the fourth day, after 20 hours, if the rice in the fermenter is smooth and silky, the rice koji is ready. Now comes the final stage. Steamed rice and boiled water are added to the rice koji and stirred. After another day of aging in a warm storage room at around 60 degrees Celsius, the amazake is finally ready.

“If the temperature is too high, it becomes sticky and gluey on the palate, and if it is too low, it turns sour. Even though some processes are mechanized, each must be manually controlled,” says Daisuke.

He says every day is a physical challenge, but he smiles merrily and says, “We’ve been doing it this way for years.”

Amanoya not only produces and sells amazake but also actively participates in koji and amazake-making courses. They are passing down the culture of fermented food to the present, which they have kept alive through the ages.

Lastly, here is a summer-only amazake shaved ice that is perfect for the approaching hotter months. The refined flavor created by the distinctive sweetness of amazake and cold ice makes this an excellent dish that will make you rediscover the magic of amazake.

We invite you to taste it in the shop’s cool setting with a sense of history.