The Silvery White Delicacy Bestowed by Sagami Bay: Shonan Shirasu

The flavor of Shonan represents Sagami Bay, one of Japan's three deepest bays

Sagami Bay extends from Jogashima Island on the Miura Peninsula in the south of Kanagawa Prefecture to Cape Manazuru on the Izu Peninsula. Marine sports such as surfing and sea kayaking are popular in the Shonan area on the coast, which bustles with many tourists in the summer.

Sagami Bay is also known as a good fishing spot, and it is believed to be home to about 1,300 species of fish among the approximately 4,000 caught in Japan. About 300 varieties among them are edible. A wide variety of fish, including horse mackerel, southern mackerel, barracuda, and yellowtail, are caught seasonally, but shirasu is the flavor that is representative of the region.

Three types of fish—sardine, Japanese anchovy and round herring—are primarily caught in the sea around Japan, and shirasu is said to be the small fry of Japanese anchovy, mostly 20 to 50 days old. It is about two to three centimeters long and is defined by a translucent, silvery-white body. Many shirasu arrive in Sagami Bay every spring, riding the Black Current that flows from west to east in the Pacific Ocean. Shirasu is fished for ten months, from March 11 to December 31 every year. Shirasu during the peak season from April to May is called spring shirasu, followed by summer shirasu from July to August and autumn shirasu from September to October.

The underwater features are also favorable for shirasu fishing. Sagami Bay is one of Japan’s three deepest bays next to Toyama Bay in Toyama Prefecture and Suruga Bay in Shizuoka Prefecture, and is 1,000 meters deep in the deepest part.

The deepest areas of the seabed store rich nutrients, which the waves carry to the shallow parts. They become the best feeding ground.

Quality-centric single-trawl operation

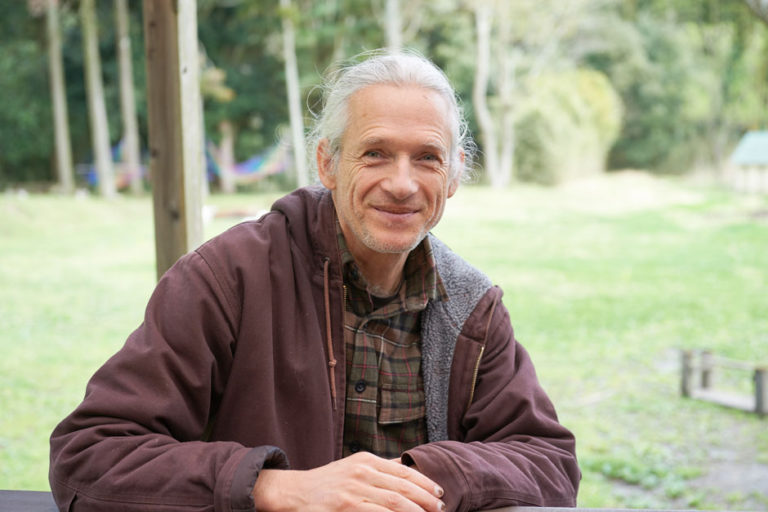

Shinichi Mizushima of Kanhama Fisheries has been contributing to Shonan shirasu fishing for about 50 years. He is the third generation of a family of fishermen. He is still active and works as the owner of the shirasu fishing boat Kanhama Maru.

During the fishing season, he leaves the Koshigoe fishing port at 5:00 a.m. every morning. He regularly moves around the fishing ground while keeping an eye on the fish-finder in the cockpit.

“Years ago, we fished by the seat of our pants. Things have become considerably easier these days,” says Mizushima.

When the finder shows a school of fish, Mizushima immediately moves the boat closer with the engine roaring. He casts the net to enclose the fish and speeds up the boat at once to haul them in as if to scoop them up. When the time is right, he retrieves the net and sorts the fish onboard. The hauled shirasu are poured into buckets and frozen with heaps of ice.

This style of fishing on a single boat is called issobiki. Nisobiki, involving two fishing boats to trawl, is practiced in other regions, but as it damages the shirasu, issobiki is mainstream for Shonan shirasu fishing.

“The size of the catch in the sea around the fishing port has decreased considerably in the last few years, but more than ten years ago we would sometimes go fishing ten times a day. The deck would be so full of iceboxes filled with shirasu that there was no place to walk.”

The shirasu are shipped directly to a processing plant near the fishing port as soon as the fishing boat lands. After being boiled on the same day, they are dried in the sun. The moist boiled shirasu, which have been dried for a few hours, are sent to the fisherman’s market along with raw shirasu. The leftovers are preserved by freezing them.

Shonan shirasu’s value changes with the times

Shirasu fishing in Shonan has a long history that dates back to the late Edo period. In those days, tatami iwashi, which was made by sun-drying shirasu scooped up in a square wooden cup, was common, and it was widely known as an Enoshima souvenir. Its non-food application expanded in the early Showa period (1926–1989). Fishing for golden horse mackerel in Sagami and Tokyo Bays was very popular back then, and salt-cured shirasu were used as ground bait.

Demand for tatami iwashi rose when Japan entered a period of high economic growth and production increased. The distribution of tempiboshi shirasu, made by sun-drying boiled shirasu, began as refrigerators became widespread in ordinary households.

In the 1980s, it became possible to boil shirasu more reliably as wood-fired cauldrons were replaced by gas cauldrons. This led to the spread of fishermen processing shirasu and selling directly to customers, eventually turning shirasu bowl into a Shonan specialty. In 1989, the Kanagawa Prefecture Shirasu Trawlers’ Liaison Council (aka, the Shirasu Council), which consisted of fishermen in the coastal areas, was established. In the 1990s, the Shirasu Council established its shirasu catch as a brand called Shonan shirasu.

Even when they entered the 2000s, they explored new possibilities while passing on the tradition of shirasu fishing to future generations.

The freshly caught taste is a luxury only Shonan shirasu can offer

“With Shonan shirasu, you can enjoy the natural taste of the fish as only salt is used when boiling them. Since Kanhama Fisheries use salt from Nagasaki Prefecture, their shirasu have a mellowness lacking in those made by other fisheries.”

The comments come from Katsuaki Shibata, the owner of Shirasuya, a restaurant specializing in shirasu dishes directly managed by Kanhama Fisheries. It has been nearly 30 years since Shirasuya opened near the fishing port, and Shibata is the main architect of the Shonan shirasu bowl boom.

Among the various shirasu dishes offered, Shirasuzukushi Teishoku (a meal with various dishes made from shirasu) is the most popular. As its name suggests, it is a sumptuous meal comprising various shirasu dishes, including shirasu tempura, tatami iwashi, boiled shirasu, and chirimen tsukudani. With the shirasu tempura, the lightness of the batter complements the shirasu well. The lingering flavor of the sea is released as you chew the umami-packed tatami iwashi. The sweet and savory taste of the tsukudani accentuates the light flavor of shirasu, and the flavor keeps you interested until the very last bite.

“The boiled shirasu are plump because they’re fresh. It’s a taste only Sagami Bay can offer as the fishing spot is a stone’s throw away,” says Shibata excitedly.

When the catch is good, a new dish called Nishokudon allows you to compare raw and boiled shirasu. It is a luxury unique to Shonan, where fresh shirasu can be sent to us directly.

“If you get a hold of raw shirasu, I want you to try raw shirasu yukhoe by dressing them in garlic soy sauce and egg yolk.”

The beauty of the Shonan shirasu, which glimmer a silvery-white color, is due to the hard work of the fishermen who operate the boats. They taste even more delicious when we think about the process they go through before being served at the table.

Shonan Shirasu

Source:Katsuaki Shibata, Shirasuya.

Peak Season

April to June for spring shirasu, September to November for autumn shirasu.

Tips

Shirasu that are about three centimeters long are the tastiest. They tend to become bitter when they grow larger, and they break down when boiled when they are smaller.

How to enjoy them

Raw shirasu make tasty yukhoe when dressed in egg yolk and grated garlic.