A Once-in-a-lifetime Experience—a Taste of Japan

To dive deeper into the world of Japanese sweets, we visited Chikara Mizukami, owner of Ikkoan, a Japanese sweet shop that opened in Myogadani, Tokyo, in 1977.

The artistry of Japanese confectioners and how it connects to the way of the samurai

When we visited Ikkoan’s kitchen, Mizukami had just finished steaming chestnuts, a great autumn delicacy.

“I am making sweets of my country.”

Mizukami started talking about what Japanese sweets are while crushing the chestnuts with a sieve.

With the sudden diffusion of Western sweets after the Meiji period (from 1868 to 1912), people started to think of Western confectioneries when they heard the word sweets. But for Mizukami, that word could only mean traditional Japanese sweets. From Mizukami’s deep insight, you can already feel his pride and devotion as a confectioner ooze out from him.

According to Mizukami, Japanese sweets were invented to enhance the taste of tea during tea ceremonies and can only be called complete when they successfully do so. Likened to the way of the samurai, the tea is the master, and the Japanese sweets are the tea’s loyal servants.

“If you can still taste the sweet in your mouth when you drink the tea, its taste will kill the tea’s flavor, will it not? My ideal sweets are those which turn the bitterness of tea into deliciousness while losing their own sweetness in the process. It is in line with samurai’s philosophy, that ‘to be a samurai is to find death.’”

Sweets with humility and fragility. That is what Mizukami loves about Japanese confectionery.

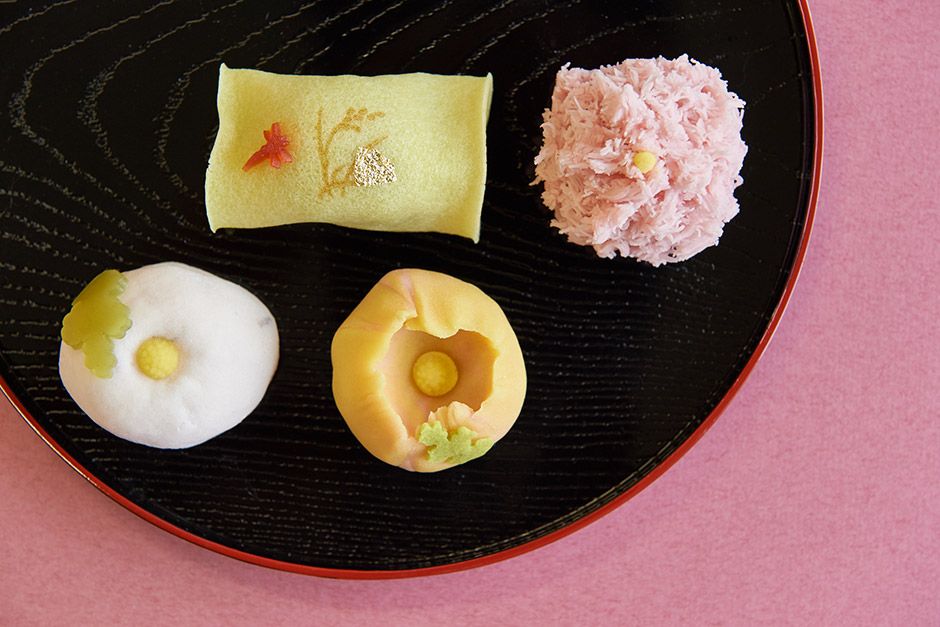

To feel their deliciousness with all five senses is the essence of Japanese sweets

Japanese sweet makers do more than just pay special attention to ingredients and techniques. They also take note of the change in seasons, landscapes and people’s emotions, and express them on the small canvas that is Japanese sweets. Their charm really comes out when you can feel and enjoy their shape, color and texture, in addition to their taste. Japanese confectioneries really do communicate the maker’s artistry.

“Even if I use the same ingredients, the sweets take on different forms depending on the season, like the shape of snow in the winter and cherry blossoms at the time of cherry blossom season in the spring, and they even have different tastes. It is not difficult to taste the sweets with all our senses. I continue to make them because I can teach others how to taste with our five senses through my craft.”

Says Mizukami, while showing us the process of making various confectioneries. It is truly exciting to watch his skillful movements as he makes the sweets one after another.

Apparently, Mizukami makes whatever inspires him at the moment, so he often cannot recreate the same confection. If he were to express autumn with a sweet right now, what would it look like? When we asked him this question he sprang into action.

First, he made small balls of unsieved bean paste made from Noto Dainagon red azuki beans, and nerikiri an (white bean paste mixed with other ingredients and colored in red and yellow) and put them on a piece of unfolded cloth.

Next, he stacked the red and yellow balls together, put them on and pressed them through a sieve, to make fine bean paste strings. The strings were picked up with tapered bamboo chopsticks and put on top of the bean paste balls, creating a confection with a perfect mix of red and yellow, much like an autumn mountain covered in colorful leaves.

Finally, Mizukami put strings of white bean paste on top, saying “This is frost. Winter is about to come to the autumn mountain.” We witnessed the moment when a unique, one and only confection was born with Mizukami’s fine artistic senses.

Sharing Japanese sweets with the world—paving the way for the survival of Japanese sweets

“So that the culture of Japanese confectioneries will survive for another 100 years.”

This is the passion behind what Mizukami does; to relay the charms of Japanese sweets to the world, beyond cultural boundaries.

He demonstrates how to make the sweets outside of Japan, and also collaborates with large confectionery manufacturers and famous chocolatiers. In November 2015, he published IKKOAN, a book archiving some of the sweets he made, based on the theme that the traditional Japanese calendar divides a year into 72 microseasons. It was published in Japanese, English and French and drew a lot of attention.

Currently, he is in touch with many pâtissiers from around the world and they sometimes visit Ikkoan, wanting to see Mizukami at work.

“Japanese sweets are part of Japan’s food culture so it is the confectioner’s mission to develop ways to survive. Being in touch with new senses that have nothing to do with Japanese sweets broadens my ideas as a sweets maker, and collaborating with Western sweets makers, may give birth to new Japanese sweets. I think I am a lone wolf, an odd one out, but it is all transient. ‘The river continues to flow yet is never the same water.’ I am just a bubble in the river of flowing Japanese sweets, so it is all about how I can pass on the art.”

His goal is to have an exhibition of Japanese sweets overseas. “When that happens, maybe it is time for me to retire,” he chuckles, but his head seemed full of ideas for his next creation.

Japanese sweets, each one hand-crafted, have a variety of flavors as endless as the confectioner’s passion. It is Japan’s food culture and it enables us to have a once-in-a-lifetime experience.